Turning JDAI’s Focus to the Deep End of the Juvenile Justice System

In the nine years since the city of St. Louis embraced detention reform, the population in its juvenile detention facility has plummeted, and the continuum of detention alternative programs has swelled. A new ethos has enveloped all corners of the city’s juvenile system dedicated to reducing the detention population as much as possible consistent with public safety.

But how are St. Louis youth faring at later stages of the juvenile court process? And how well is the city doing in minimizing the use of correctional commitments and other residential placements for youth who do not pose a significant threat to public safety?

Beginning in late 2012, St. Louis leaders set out to dig deep and find out, joining the first cohort of sites in the Casey Foundation’s new effort to broaden the focus of JDAI to the dispositional (or “deep”) end of juvenile justice. St. Louis and the other five pilot sites — Bernalillo County (New Mexico), Jefferson Parish (Louisiana), Lucas County (Ohio), Marion County (Indiana) and Washoe County (Nevada) — spent all of 2013 mobilizing deep end study groups and conducting an extensive quantitative and qualitative assessment to better understand local dispositional trends and to identify opportunities for safely reducing placements.

The ultimate impact of their efforts will not be known for some time — the sites are just now developing their action plans. But the assessment process revealed a number of important lessons.

First, all six sites found that many youth who pose minimal risks to public safety are nonetheless being removed from their homes and placed into correctional institutions or other residential facilities. Thanks in part to their work in JDAI, all six sites had already reduced commitments significantly before launching their deep end efforts. However, the assessment process made clear that many opportunities remain to safely reduce residential confinement below current levels.

Second, all of the participating sites have found that unnecessary placements are occurring both at initial disposition and through violations of probation. Every site identified room for improvement in the use of risk assessments to determine initial dispositions, and every site found that a substantial share of placements — at least 30 percent — stemmed from probation violations rather than new offenses.

Third, the sites’ efforts to reduce deep end placements rely on many of the same tools and values used in JDAI — including collaboration, data analysis, objective decision making and an intentional focus on racial/ethnic equity — but it is more complex. Compared with detention reform, sites are finding that reducing dispositional placements requires more elaborate and sophisticated data analyses, a top-to-bottom review of risk and needs assessment procedures, far greater attention to frontline probation practice and more intensive efforts to engage and support families.

Despite the challenges, sites are making progress and building momentum.

“It’s been a lot of work. Your brain is constantly working,” reports Cathy Horejes, Chief Deputy Juvenile Officer in the St. Louis City probation department. “But it’s just a natural flow,” Horejes says. “Once you’ve improved the front end of your system [through JDAI], I think you need to critically look at the back end. You need to ensure that you’re not just looking at the data, but that you’re taking the next step and doing something with the data. That’s what the deep end focus has done for us.”

• • •

By December 2013, when teams from the six deep end sites convened for an inter-site workshop, all had completed their assessments, boiled down the results into PowerPoint presentations and shared the findings with their local collaboratives.

In St. Louis, the data revealed that half of all placements stemmed from misdemeanors or probation violations. Just 13 percent of the placements were for violent felony offenses. Indeed, the data showed that St. Louis youth had a greater likelihood of out-of-home placement for a probation violation than a violent felony.

Equally powerful, says Cathy Horejes, have been the insights gleaned from surveys and interviews with youth, families, public defenders, service providers, probation staff and others. Many statements were positive, but others were critical, and they made a powerful impression on her staff of 35 probation officers. “To hear what came out of people’s mouths was like, ‘wow,’” Horejes says. “Those were learning moments.”

In Lucas County, Ohio, the deep end data analysis revealed two eye-opening trends. First, while the overall number of commitments and residential placements has fallen in recent years, the decline has lagged an even larger drop in arrests and referrals. In fact, for youth who are arrested, the odds of being placed in a residential facility have grown by more than half since 2008.

“When we saw that the commitments were rising in relation to arrests and referrals, it was a big wow,” reports Rachael Gardner, the local deep end coordinator. “It provided a different frame.”

The Lucas County assessment also revealed a striking racial disparity in placements. Whereas the proportion of African-American youth holds roughly steady (about 60 percent) at most decision points — including arrests, detention admissions, petitions, adjudications and probation placements — 92 percent of youth sent to residential treatment centers and 94 percent of youth sent to state training schools are African American.

“We didn’t expect that our system wouldn’t have disproportionality and disparity,” says Gardner, “but seeing that jump at the point of out-of-home placement, that was surprising.”

• • •

In early 2014, the pilot deep end jurisdictions are devising action plans and taking initial steps to address the issues they have identified. Reviewing risk and needs assessments is a focus for all sites — both the design of the tools, and the way they are used to inform the decision-making process.

In St. Louis, local leaders are reexamining their risk assessment tool. Until now, Horejes explains, staff have seen the tools “as a task to complete, not something to help them in real decision making.”

To limit placements stemming from probation violations, St. Louis has begun requiring probation officers to convene a meeting with the youth, family, probation leaders and other partners before filing a probation violation. In May 2014, Horejes hired a former child protection worker to train probation staff on how to conduct these team decision-making meetings effectively.

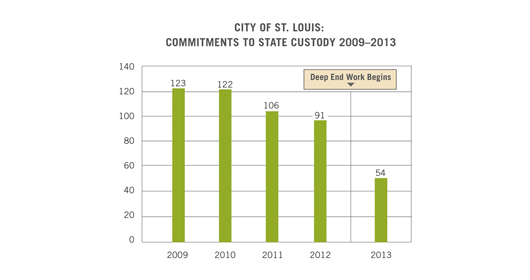

St. Louis is already showing a dramatic drop in placements. Just 54 city youth were committed to state custody in 2013, down from 91 in 2012 (and more than 100 each year from 2008 to 2011). Horejes attributes most of the decline to the arrival of a new presiding juvenile court judge, David Mason, a champion of deep end reform. In addition, Horejes says, through training sessions on family involvement and through their involvement in the assessment process, the deep end efforts are beginning to influence how probation staff work with court involved youth.

In Lucas County, local leaders are working with the National Council on Crime and Delinquency to design a new dispositional matrix to guide initial placement decisions. In addition, Lucas County has opened a new day treatment program for probation youth exhibiting continuing conduct problems who might otherwise be placed in a residential facility.

“The work is fantastic,” says Gardner. “It really lifts up what’s next for your jurisdiction, and it’s led to some really important conversations.” Asked what advice she would offer to other JDAI jurisdictions considering whether to apply and become a deep end site, Gardner responds: “Come on. Jump in with us. Jump into the deep end, because it’s totally worth it.”