The Number of Youth in Secure Detention Returns to Pre-Pandemic Levels

“The New Normal” or “The Old Status Quo?”

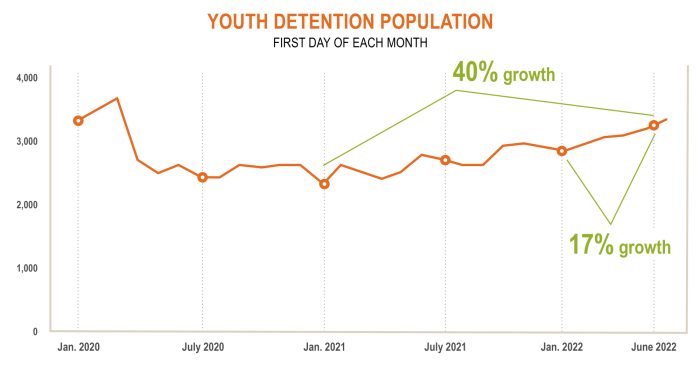

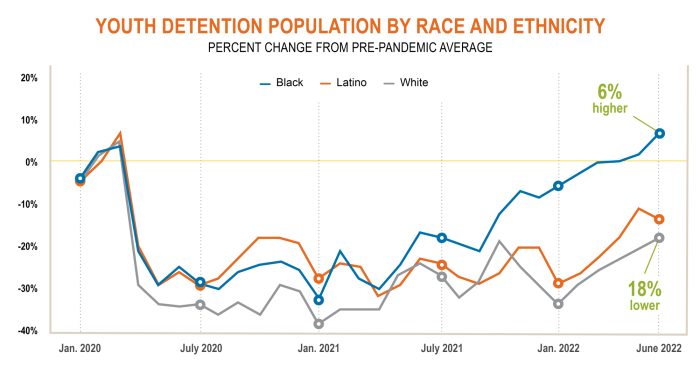

A monthly survey of youth justice agencies by the Annie E. Casey Foundation finds that the dramatic drop in youth detention that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic has evaporated. After having fallen as much as 30% in the first few months of the pandemic, the number of youth held in juvenile detention had risen almost to its pre-pandemic average as of June 1, 2022 — and for Black youth, the number detained was 6% higher. In total, the June figures represent an increase of more than 40% since January 2021 and 17% just since the start of 2022.

Moreover, although the youth detention population is now similar in size to what it was before the pandemic, significant and concerning changes have occurred beneath the surface:

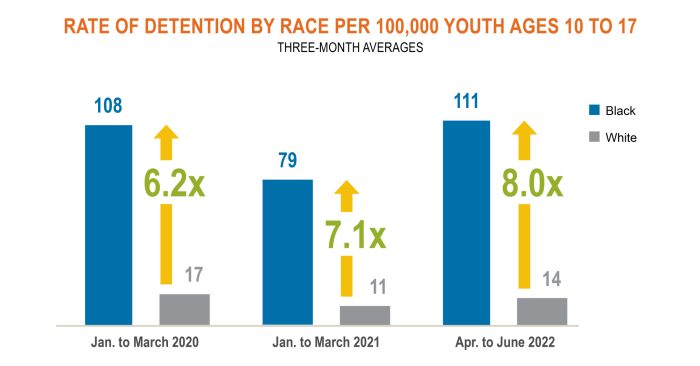

- The disproportionate use of detention for Black youth — already distressingly high before the pandemic — has increased. From January to March 2020 (the months just before the pandemic) Black youth were detained at more than six times the rate of white youth. Since then, that disparity has widened — both when the overall youth detention population was falling through early 2021, and when it was rising over the past 15 months. As a result, from April 2022 to June 2022, Black youth were detained at eight times the rate of white youth.

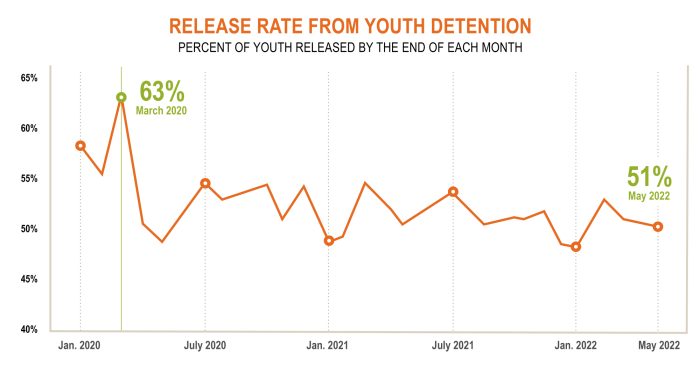

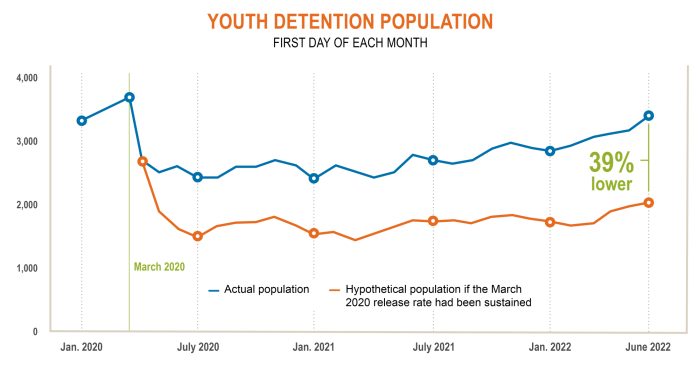

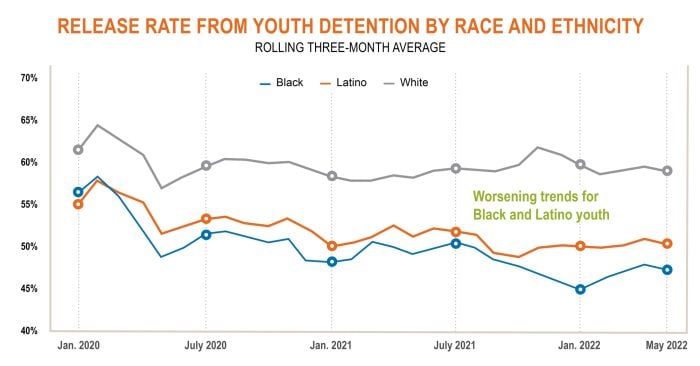

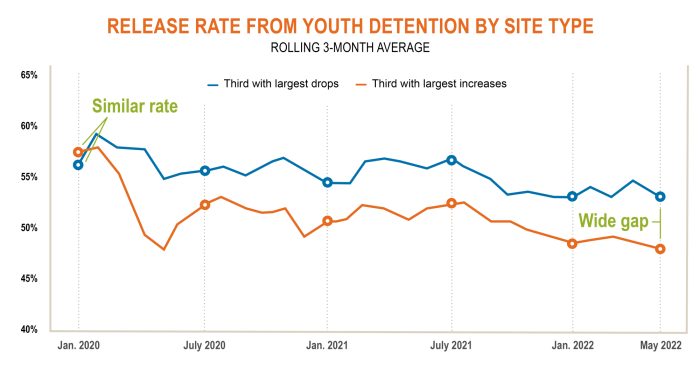

- Detention stays have grown longer. A protracted slowdown in releasing youth from detention since the early days of the pandemic has kept the detained population higher than it should be — almost 40% higher as of June 1, 2022. The release rate slowed much more for Black youth than for white youth in 2021 and 2022 —leading directly to the worsening racial disparities in who is detained overall.

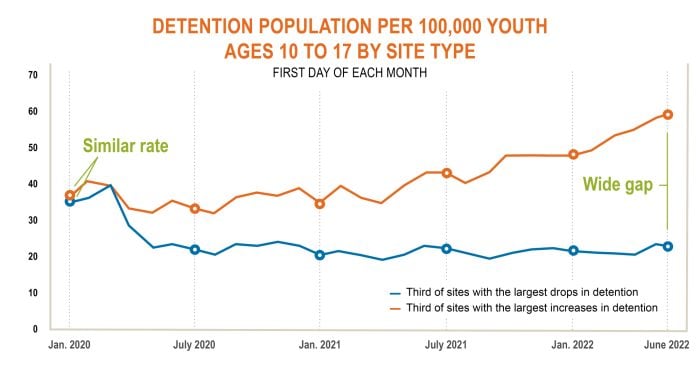

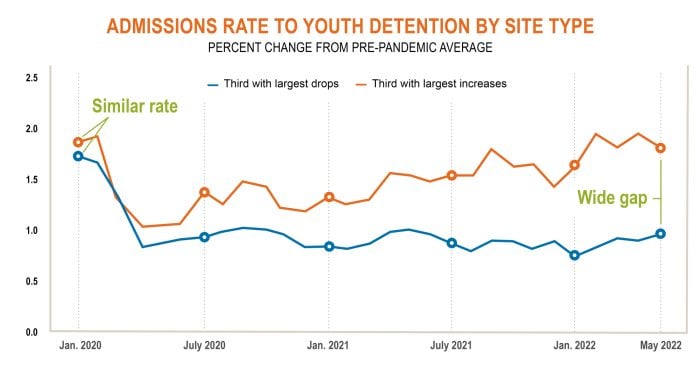

- Jurisdictions that had similar patterns of detention use before the pandemic began have adopted dramatically different patterns over the course of the pandemic. As a result, the one-third of survey sites that have reduced detention the most have sustained a 37% reduction from their pre-pandemic average. In contrast, the one-third of sites that have increased detention the most have seen a 56% increase, all of which has occurred in the past 13 months (since May 2021).

Given that even a short stay in detention can have profound and potentially lifelong negative consequences for the young people involved, these findings raise alarms for the well-being of thousands of young people and challenge juvenile justice systems across the country to detain young people as a last resort.

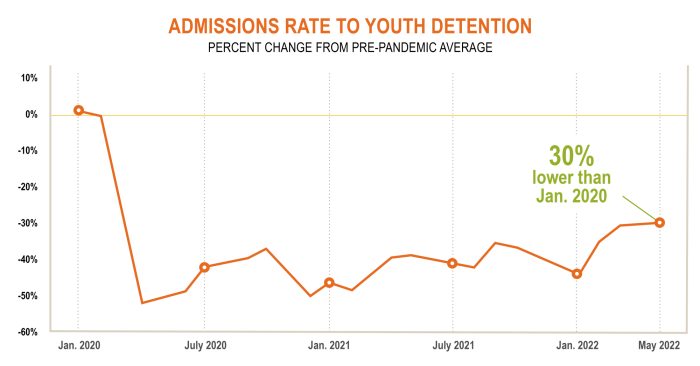

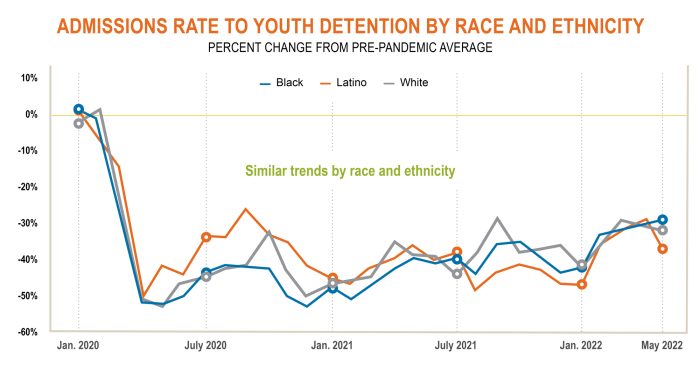

The findings come at a time when many practitioners are reporting heightened concerns about safety in their communities or concerns about rising youth crime. “The survey findings, however, do not indicate a surge of young people coming into detention across the board,” says Nate Balis, director of the Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group. “The data don’t give us reason to believe that rising crime explains overall population gains in detention. In fact, the rate of admissions is considerably lower in 2022 than it was in the early months of 2020.”

Charts and Findings on Youth Detention

After a rapid decline when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the spring of 2020, the youth detention population began rising in spring 2021 and has returned to its pre-pandemic level in summer 2022.

When the pandemic began in March 2020, the number of detained youths in survey sites plunged from an average of more than 3,500 from January to March 2020, to just 2,514 in May 2020 — a drop of almost 30% in just nine weeks. Through the school closings and racial reckoning of the next 12 months, the population stayed close to that low level through May 2021. But the population has grown more than 30% since then (40% since January 2021) and 17% just since the start of 2022. On June 1, 2022, there were 3,346 young people in detention in survey sites — slightly higher than the January 1, 2020, population of 3,331.

The rate of admissions to detention centers is still much lower than it was before the pandemic. The population has returned to its old level because young people are staying in detention longer.

The rate of admissions to detention has dropped by 30% since the beginning of 2020. That reduction has not resulted in a smaller detention population, because of a slowdown in the pace of releases. In other words, those young people who are getting detained in 2022 are staying longer than youth who were detained before March 2020. The slowdown in releases has fully offset the reduction in admissions, resulting in a detained population that is roughly the same size it was before the pandemic.

The brisk pace of releases in March 2020 showed the system’s decision-makers were capable of speedy case processing.

If youth justice systems had been able to maintain the March 2020 release rate in the months since then, the detained population would have been 39% lower on June 1, 2022. In other words, roughly two of every five young people in detention centers on June 1, 2022, would not have been there if youth justice systems had maintained the pace of releases that they achieved 26 months earlier.

The slowdown in release rates of youth from detention has fallen especially hard on Black youth. As a result, the growth of youth detention since its lows early in the pandemic has predominantly affected Black youth.

On June 1, 2022, the number of Black youths in detention was 6% above its average level from January to March 2020 (before the pandemic). The number of white youths in detention was 18% lower than its pre-pandemic average.

This is not due to differences in the trend of admissions between Black and white youth, which have been similar throughout the course of the survey. Rather, the increasing disparity is due to the release rate slowing down much more for Black youth than for white youth. The release rate also slowed more for Latino youth than for white youth, but the slowdown has affected Black youth most severely.

In the survey jurisdictions that provide detention data disaggregated by race and ethnicity, Black youth were more than six times as likely to be in detention than white youth before the pandemic. That disparity has grown when the total detained population was:

- falling from early 2020 to early 2021; and

- rising from early 2021 to June of 2022.

Black youth account for 18% of the age 10–17 population in survey sites but accounted for 68% of the growth in youth detention from its post-pandemic low point in January 2021 to June 2022.

Over the course of the pandemic, jurisdictions that initially had similar patterns of detention use now look very different from each other.

Comparing survey sites that have seen the largest reductions in detention with those that have seen the largest increases reveals a large and widening divide in the way that different jurisdictions have responded to the past two years. Adjusted for the size of their youth populations, these sites entered the pandemic with similar rates of detention, similar admissions rates and similar release rates. But the paths they have taken since then have been strikingly dissimilar.

- At the start of the pandemic, almost all survey sites reported steep drops in admissions. The one-third of sites with the largest reductions in detention use sustained that drop in admissions, while keeping the pace of releases close to pre-pandemic levels. As a result, as of June 1, 2022, these sites had slashed their detained populations by 37% below their pre-pandemic average.

- The third of sites with the largest increases in detention did not sustain the drop in admissions. Even more notably, their pace of releases slowed down substantially. Consequently, they were detaining 56% more young people on June 1, 2022, than they did before the pandemic.

All the differences in detention use across these groups of sites as of June 2022 emerged over the past 26 months, based on different local choices about how to respond to conditions that have affected almost every community during the pandemic era.

“The big question early in the pandemic and following George Floyd’s murder in 2020 was whether there had become a new normal for juvenile justice of dramatically fewer youth in detention and greater equity among Black, Latino and white youth,” Balis says. “Over two years later, we’re seeing that progress take hold for a third of the places in our survey. Unfortunately, for another third of places, we’re seeing trends worse than the old status quo: more youth admitted to detention, more youth staying longer in detention and Black youth feeling the brunt of both.”

About the Survey

This survey, conducted each month since the pandemic began in March 2020, is aimed at assessing the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on juvenile justice systems around the country. This analysis is based on reports from 123 jurisdictions in 32 states, representing 26% of the nation’s youth population (ages 10–17), for which data have been submitted for every month from January 2020 through June 2022. For the numbers that are disaggregated by race, the analysis is based on reports for 116 jurisdictions across 31 states containing 24% of the youth population. The Monthly Detention Survey represents a non-random sample of youth justice systems in the United States, and aggregates from this survey should not be regarded as national estimates.

Read more about how the survey is conducted and see previous data releases