States Spending Little on Prevention Services, Survey Finds

In its 11th national survey to identify trends in child welfare funding sources and agency spending, Child Trends finds that child welfare agencies increased their spending by 2% over the past decade, with a significant portion of that spending going to place young people away from their own homes. The comprehensive report, produced with support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and Casey Family Programs, tracks expenditures over a decade, updating previous surveys to include data from state fiscal year (SFY) 2018.

Child Welfare Financing SFY 2018 shows agencies spent $33 billion nationwide during this period, with resources culled from multiple funding streams. While ratios vary widely from state to state, most agencies use a mix of federal, state, local and other sources — each with distinct purposes and requirements. Understanding this financing system is key to analyzing how states decide to care for children at risk of maltreatment and the challenges and opportunities public systems face in carrying out their responsibilities.

In addition to providing insights into how agencies finance and prioritize their work, the most recent data — collected in 2019 and 2020 — also capture a significant moment for the child welfare field, just prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the implementation of the Family First Prevention Services Act and a national reckoning on racial equity. Agency leaders and policymakers can use these data as a baseline to track the effects of these factors on future spending.

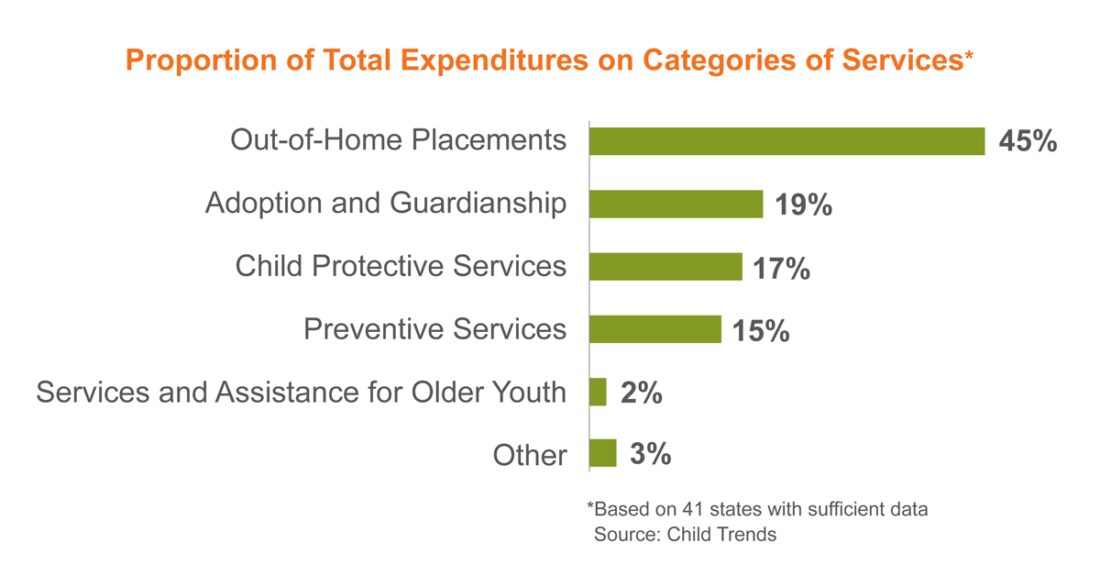

As in previous years, the SFY 2018 survey found that out-of-home placements continued to be a financing priority for agencies — making up 45% of total federal, state and local child welfare spending, with just 15% going toward preventive services that support families with the goal of keeping children safe in their homes.

Family First’s emphasis on prevention is a start to shifting that trend, noted Leslie Gross, director of the Casey Foundation’s Family Well-Being Strategy Group. She says that families can’t afford to wait for priorities to shift. “The pandemic has amplified the urgent need to support families so they can stay together — and these data show we can do much more to reorient our approaches to keeping young people with their families and in their communities,” Gross says.

The survey also found:

- Most child welfare agency spending on preventive services funded skill-based programs for parents, caseworker visits and administration, with a smaller portion focused on substance abuse and mental health services.

- Few states were able to report how much of their spending went to evidence-based practices, a key focus of the Family First Act.

The report includes reflective questions for state system leaders to ask about their spending, including:

- Does our spending reflect our priorities and values?

- How does the way we finance child welfare perpetuate racial inequity and disproportionality in our system?

- How can we use the Family First Act and other recent legislation to maximize opportunities to finance child welfare differently?

- Are child welfare systems achieving desired results for all children and families?

- Are we missing resources available to our agency?

Learn about how child welfare agencies can conduct a fiscal analysis for Family First