Reliance on Incarcerating Youth Offenders Not Paying Off for States, Taxpayers or Kids, Report Finds

Locking up juvenile offenders in correctional facilities, which costs states a yearly average of $88,000 per youth, is not paying off from a public safety, rehabilitation or cost perspective, according to a new report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The report documents four decades of scandals and lawsuits over abusive conditions in juvenile institutions and reinforces the growing consensus among experts that the current incarceration model provides little public safety benefit. Its release, at a time when states nationwide are struggling with enormous budget deficits and looking for ways to trim spending, also highlights an emerging trend in which at least 18 states have closed more than 50 juvenile corrections facilities over the past four years.

No Place for Kids: The Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration is the most comprehensive recent analysis of research and new data on the effectiveness and costs of juvenile incarceration. The report concludes that there is now overwhelming evidence that the wholesale incarceration of juvenile offenders is a failed strategy for combating youth crime because it:

- Does not reduce future offending by confined youth: Within three years of release, roughly three-quarters of youth are rearrested; up to 72%, depending on individual state measures, are convicted of a new offense.

- Does not enhance public safety: States which lowered juvenile confinement rates the most from 1997 to 2007 saw a greater decline in juvenile violent crime arrests than states which increased incarceration rates or reduced them more slowly.

- Wastes taxpayer dollars: Nationwide, states continue to spend the bulk of their juvenile justice budgets – $5 billion in 2008 – to confine and house young offenders in incarceration facilities despite evidence showing that alternative in-home or community-based programs can deliver equal or better results for a fraction of the cost.

- Exposes youth to violence and abuse: In nearly half of the states, persistent maltreatment has been documented since 2000 in at least one state-funded institution. One in eight confined youth reported being sexually abused by staff or other youth and 42% feared physical attack according to reports released in 2010.

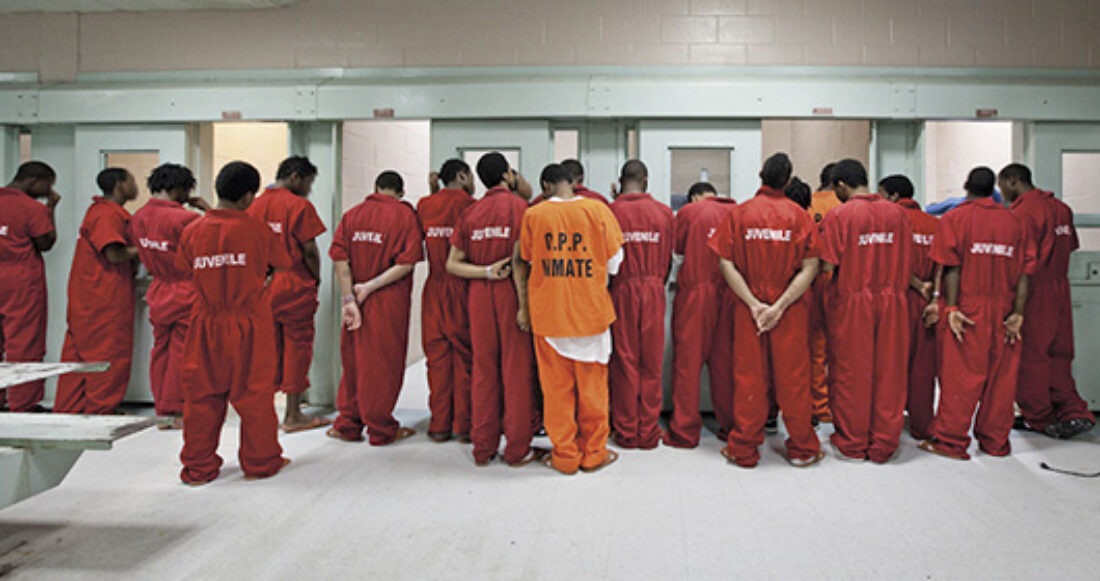

Roughly 60,500 U.S. youth – disproportionately young people of color – are confined in juvenile correctional facilities or other residential programs on any given night, according to an official national count of youth in correctional custody conducted in 2007. That is more adolescents than currently reside in cities like Baltimore, MD and Nashville, TN.

The report also tracks a notable trend in recent years among a growing number of states that have shuttered youth incarceration facilities and substantially shrunk the number of confined youth, often prompted by budget crises or abuse scandals. No Place for Kids highlights six recommendations for how state and local juvenile justice officials can alter youth incarceration patterns and improve system outcomes, noting that the recent declines in youth confinement have not generally been accompanied by comprehensive reforms that maximize both public safety and positive youth development.

“The traditional approach of locking up youth offenders wholesale – even those with limited histories of serious or violent offending – has continued for decades without any evidence that it helps kids or protects the public,” says Bart Lubow, director of the Juvenile Justice Strategy Group at the Annie E. Casey Foundation and former director of Alternatives to Incarceration for New York State. “This report highlights the crucial challenges facing the youth corrections field. Our hope is that the research will serve as a catalyst for developing more effective and efficient juvenile justice strategies.”