Pierce County Youth Probation: Few Youth Need Out-of-Home Placement

Photo courtesy of Pierce County Juvenile Court

Washington State’s Pierce County — home to Tacoma — demonstrates that most youth who get in trouble with the law can get back on track without incarceration. Deploying strategies rooted in the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s vision for transforming juvenile probation, the county offers an example of what is possible when youth justice systems build strong community partnerships and pursue changes designed to maximize connections and opportunities for young people to become successful adults.

Compared to the national average, Pierce County sends a dramatically smaller percentage of its young people to court-ordered correctional facilities and other residential institutions, relying instead on probation and community partnerships to support young people with serious and complex cases. The county’s policies and practices recognize that young people are more likely to thrive in their own communities with stable connections to positive adults and activities than in institutional confinement. In 2019, the last year of available national data, the county’s reliance on confinement was less than one-third of the national rate.

In Pierce County, juvenile probation counselors (called officers in most jurisdictions) work with youth with serious offenses and significant needs who — if not for the support and structure of probation — would be institutionalized. How do counselors have time for the intensive mentorship, guidance and relationship building this group of young people requires? The county follows a framework to focus its probation resources only on the young people who need them to succeed in a community setting and avoid the harms of incarceration.

A Framework That Focuses Juvenile Probation Resources

The county uses two complementary strategies to focus probation resources.

First, Pierce County tries to maximize the number of young people diverted from formal processing to community-based responses, based on specified minimum requirements that a case must meet before a youth is put on probation. This frees up probation resources and recognizes the abilities of local organizations and people to support their youth. “The youth justice system has been a catch-all for dealing with behaviors that are normal parts of adolescent development,” says Kevin Williams, probation manager for Pierce County Juvenile Court. “Young people need positive opportunities and connections to thrive, not criminal records.”

Second, probation officers reserve probation recommendations for youth with significant needs and serious offenses, many of whom would have otherwise been incarcerated.

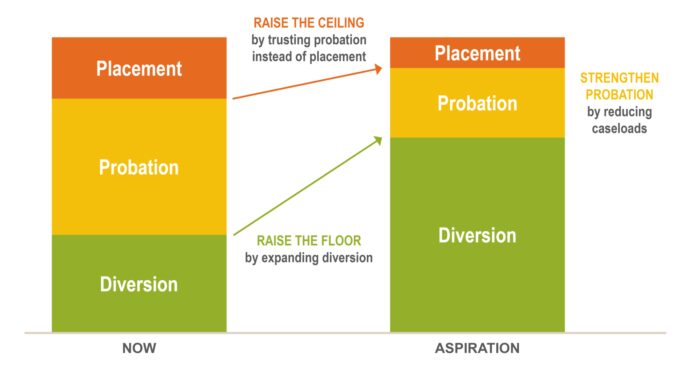

The following image illustrates the framework. It depicts raising the floor that separates diverted youth from those on probation and raising the ceiling that separates youth on probation from those in custody. The strategies work in tandem. Unless jurisdictions raise the floor, their probation caseloads will be too large for officers to build meaningful relationships with young people with significant needs and serious offenses. With smaller caseloads and the right approach, probation can raise the ceiling, which means relying on probation staff to work with youth who would otherwise be institutionalized. A jurisdiction needs to enact both strategies to realize the potential for diversion and probation to foster community connections and opportunities, support long-term behavior change and avoid the cost and danger of excessively punitive responses.

Pierce County has undertaken these changes with comprehensive and collaborative planning involving community-based organizations, young people, families, attorneys, judges and a host of other partners.

Keeping Young People Connected to Community, Not Courts

The Pierce County Juvenile Court informally handled 73% of the case referrals it received in 2021 through a diversionary process, leaning on community responses rather than legal sanctions and court oversight to help young people get back on track. In the parlance of the framework, Pierce County was able to raise the floor of its probation population by diverting 73% of its case referrals. This statistic is significant because a growing body of research over the last 25 years indicates that young people whose cases are handled informally stay in school longer and are less likely to be arrested than their peers who are formally prosecuted.

Inspired by that research, Pierce County analyzed its own data in 2018 and found that three-quarters of the more than 5,000 young people whose cases were diverted between 2012 and 2016 had no arrests for new offenses in the two years after their diversion. As the county expanded its diversion efforts and brought in community partners to help design and deliver services and opportunities, those results got even stronger. As of December 2020, more than 80% of diverted youth had no new arrests two years after being diverted; 93% had no felony arrests.

Compared to the court system, diversion offers young people more immediate and constructive responses to their actions. For example, young people charged with domestic violence, such as a physical altercation with a parent or vandalism of family property, can be directed to a nonprofit partner that provides respite care and services for families in crisis, modeled after an approach used in King County, Washington. This is an early and swift intervention — typically within 24 to 48 hours of arrest — in contrast to formal processing, which often creates weeks-long delays in services and unnecessary involvement in the justice system.

Examining diversion data can promote more equitable treatment of young people of color in the juvenile justice system as well. In 2019, an internal analysis found that Black youth in Pierce County were diverted from juvenile court far less frequently than their white peers, which is true across the nation. Williams and his team acted on the data to forge and strengthen partnerships with neighborhood-based organizations in Black communities. These local groups and the University of Washington designed diversion opportunities specifically for Black youth that offered them connections to positive adults and activities close to home.

“Expanding diversion is only part of the work required to focus valuable and limited probation resources on the right youth,” says Danielle Lipow, a senior associate in the Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group. “While expanding diversion essentially raises the floor for who gets probation, it is equally important to raise the ceiling on the probation population, which can only happen when systems begin to trust probation with young people who are currently being removed from their homes and families.”

Trusting Probation Officers to Work With Youth Who Would Otherwise Be Institutionalized

Handling more serious cases through probation rather than placement (raising the ceiling) has required practice changes within the department. For instance, probation officers rely more on opportunity-based probation to help youth build skills, develop responsibility and avoid being arrested again. This approach is rooted in research that indicates young people respond better to rewards for progress toward goals than they do to threats of punishment. Probation staff, young people and their caregivers work together to develop a case plan and define weekly goals for which youth can earn tangible positive reinforcement. Another practice change has been for probation officers to team up to help one other to stave off the occupational stress that could result from working intensively to support youth with complex lives and needs.

Williams credits the front-line juvenile probation counselors and supervisor team for creative thinking and embracing partnership with young people and families. “We’ve empowered staff to speak freely, and as a result, they feel heard, respected and treated fairly so they can show up for the work and thrive,” Williams says.

Pierce County probation counselors work closely with an infrastructure of more than 20 community-based partners, an advisory council of young people’s family members and a group of trained mentors called credible messengers whose life experiences allow them to relate to and reach young people engaged in risky behavior. Unlike many of its peers, the county rarely sends its youth to state-run correctional facilities, residential treatment centers or group homes.

Pierce County’s data analysis showed the need for specific strategies to ensure that youth of color had the opportunity to succeed on probation instead of placement. In 2016, for example, after the probation department recognized that Black youth were more likely to be confined than white youth, administrators created Pathways to Success, a nine- to 12-month specialized probation program for Black youth. Pathways encourages probation counselors to work with families to support and guide youth most at risk of confinement with comprehensive support, including credible messenger mentors who help the young people address the challenges they face. During a session with a mentor, a young participant reflected: “I appreciate how you got really into detail about your personal life, and you gave us advice about how to fix our personal lives. I think of this as an actual learning experience.”

In 2016, Washington State laws changed to give courts more discretion to use probation instead of out-of-home placement for youth with serious offenses such as robbery. Pierce County seized this opportunity and has asked the court to entrust probation with an increasingly larger percentage of youth with more serious cases. Of all youth with charges in that category, the share who received probation instead of incarceration as a disposition grew from 40% in 2016 to 77% in 2021.

The Takeaway

To transform youth probation, systems need to rethink the roles of probation staff and the population of young people on probation caseloads. By diverting less serious cases outside the system and concentrating on more serious cases, systems can focus limited probation resources on helping more young people succeed in the community while keeping the community safe.

“Pierce County has always been a strong system that strived for the best possible results for young people and their families and communities, guided by research and a resolute focus on racial equity and community safety,” says Lipow. “By leaning into partnerships with young people, families, communities and probation staff, Pierce County continues to prove that justice is best served when the community leads.”

Related Juvenile Probation Resources

Pierce County: Trailblazer for probation transformation

Incentives inspire positive behavior change in youth on probation