Kids in Concentrated Poverty Data Snapshot

Percentage of kids in concentrated poverty worsens in 10 states and Puerto Rico

The Annie E. Casey Foundation today released “Children Living in High-Poverty, Low-Opportunity Neighborhoods,” a KIDS COUNT® data snapshot that examines where concentrated poverty has worsened across the country despite a long period of national economic expansion.

The report, which analyzes the latest U.S. Census data available, finds that between 2008–2012 and 2013–2017, 10 states and Puerto Rico saw increases in the percentage of children living in concentrated poverty. By contrast, 29 states and the District of Columbia saw decreases in the share of children in concentrated poverty, and 11 states experienced no change.

What is concentrated poverty?

The effects of concentrated poverty begin to appear once neighborhood poverty rates rise above 20% and continue to grow as the concentration of poverty increases up to 40%. Because 30% lies between the starting point and leveling off point for negative neighborhood effects, the figure is often used to define “concentrated poverty.”

Concentrated poverty and child development

Growing up in a community of concentrated poverty — that is, a neighborhood where 30 percent or more of the population is living in poverty — is one of the greatest risks to child development. Alarmingly, more than 8.5 million children live in these settings. That’s nearly 12 percent of all children in the United States.

Children in high-poverty neighborhoods tend to lack access to healthy food and quality medical care and they often face greater exposure to environmental hazards, such as poor air quality, and toxins such as lead. Financial hardships and fear of violence can cause chronic stress linked to diabetes, heart disease and stroke. And when these children grow up, they are more likely to have lower incomes than children who have relocated away from communities of concentrated poverty.

“We all know that children thrive when they grow up in neighborhoods with high-quality schools, abundant job opportunities, reliable transportation and safe places for recreation, yet across the country, millions of our kids are living in poverty,” said Lisa Hamilton, the Casey Foundation’s president and CEO. “Following such a long period of national economic growth, we should see widespread poverty reduction for more communities. It is imperative that we implement policies to revitalize the children and families that remain left behind.”

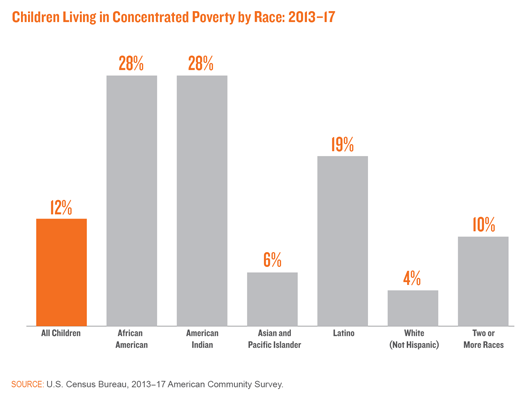

Concentrated poverty and race

The data report outlines solutions to address concentrated poverty and challenges leaders to confront issues such as the far-reaching effects of racial inequities and inequality. African American and American Indian children are seven times more likely to live in poor neighborhoods than white children and Latino children are nearly five times more likely, largely as a result of legacies of racial and ethnic oppression as well as present-day laws, practices and stereotypes that disproportionately affect people of color. Even relatively wealthy states like Texas and New York have a large share of children of color living in concentrated poverty.

State data on concentrated poverty and children

Additional key findings in the report include:

- Ten states and Puerto Rico saw the percentage of children living in concentrated poverty increase: Alaska, Delaware, Louisiana, Maine, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

- Eleven states saw no progress: Alabama, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Virginia, Vermont and Wisconsin. The other 29 states and the District of Columbia saw decreases.

- Half of the total number of Latino children living in concentrated poverty in America are in just two states: Texas and California.

- Half or more of Native American kids in Arizona, New Mexico, North Dakota and South Dakota are living in concentrated poverty. Arizona alone is home to more than a quarter of all American Indian children living in concentrated poverty (56,000 children, 28 percent of the national total).

- In Michigan, half of the state’s African American children live in high-poverty neighborhoods; the figure is 40 percent or higher in Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and the District of Columbia.

Areas of concentrated poverty in America

States in the South and West tend to have high rates of children living in concentrated poverty, making up 17 of 25 states with rates of 10% and above.

Overall, urban areas have both the largest number and share of children living in concentrated poverty: 5.4 million, or 23% of all kids in cities. About 11% of kids (1.2 million) in rural areas live in poor communities, while 5% of suburban kids (2 million) do.

Solutions to child poverty in America

“Solutions to uplift these communities are not far out of reach, and they would have significant positive effects both for children and youth and for our country as a whole,” said Scot Spencer, associate director of advocacy and influence at the Casey Foundation. “Strong neighborhoods foster stable families and healthy children.”

The Casey Foundation urges leaders — from the national and state level to counties, cities and other local settings — to act now to help families lift themselves out of these circumstances. Policies at the community, county and state levels that can have a significant impact on the lives of children in struggling families include:

- Supporting development and property-ownership models that preserve affordable housing, such as community land trusts and limited-equity cooperatives.

- Ending housing discrimination based on whether a person was formerly incarcerated or is using a federal housing voucher.

- Assisting low-income residents in paying higher property taxes that often come with new development/redevelopment or with a family’s relocation to a more affluent area.

- Expanding workforce training that is targeted to high-poverty, low-opportunity communities.

- Requiring and incentivizing anchor institutions to hire locally and contract with businesses owned by women and people of color.

- Developing and funding small-business loan programs that serve entrepreneurs in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color — or people that traditional lenders tend to reject, such as individuals with poor credit or criminal records.

Read or download the data snapshot