Ohio County Expands Diversion for Youth With Misdemeanor Charges

The Casey Foundation awarded Lucas County, Ohio, which includes the city of Toledo, a probation transformation grant to test part of a new approach in juvenile probation. The Foundation believes that a significant percentage of those youth who would be customarily placed on probation would be better served if their cases were diverted from court.

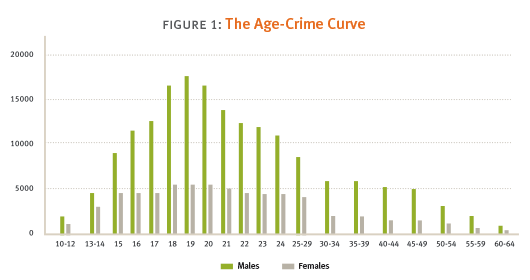

Many juvenile courts across the country routinely sentence young people with misdemeanor-level offenses to probation, or even out-of-home placement. Research, however, is clear that most adolescents will age out of delinquent behavior, even without formal juvenile justice system involvement (see figure 1).

Furthermore, there is no conclusive evidence that the traditional approach to juvenile probation — focused primarily on a young person’s compliance with court orders and an officer’s ability to track that compliance — is an effective method for protecting public safety and improving outcomes for youth and families. Rather, the traditional approach has often acted as a gateway to incarceration.

This year, the Lucas County Juvenile Court is giving more youth with misdemeanor-level charges the opportunity to avoid formal system processing. For Demecia Wilson, Lucas County’s juvenile probation administrator, the goal is to deliver “the right response at the right time” that still ensures public safety.

Lucas County is betting on its ability to leverage its community and family partnerships to provide more services to youth and families without the requirement of a court order. It is undertaking initiatives such as mapping community assets in order to partner with community-based organizations rooted in the neighborhoods where large numbers of system-involved youth reside. More effective community-based interventions are a key component of Lucas County’s approach.

Lucas County’s work also has involved a significant restructuring of its staff and resources. In 2016, the county expanded its community-based assessment center, which now screens all youth charged with misdemeanor-level offenses, including school-based referrals.

Wilson noted that the assessment center’s more systematic and structured approach to decision making is reducing racial disparities among youth who are under consideration for diversion. Better assessment has reduced the number of school-based referrals that lead to formal charges and reduced probation caseloads.

“The probation officers have more time to spend with higher-risk kids,” Wilson says. “So relationships can go deeper and they can build up those kids’ skills.”

If the percentage of misdemeanor cases in Lucas County stays consistent with 2011–2015 numbers when misdemeanors represented an average of 72 percent of cases filed for formal processing, one can extrapolate that youth involved in approximately 3,000 cases will be considered for diversion as a matter of policy. This is nearly 2,000 more cases than in the past, with half of those likely to result in diversion.

A newly formed unit called Misdemeanor Services will handle most of the remaining cases, with a youth’s system involvement ranging from 30 to 90 days.

Jurisdictions within Ohio and elsewhere have observed Lucas County’s Assessment Center or requested more information about it. Wilson thinks her county’s model is transferrable and scalable and welcomes inquiries about replication.

The prevalence of offending tends to increase from late childhood, peak in the teenage years (from 15 to 19) and then decline in the early 20s. This bell-shaped age trend, called the age-crime curve, is universal in Western populations.

Check out another resource on reforming juvenile probation