Child Poverty Rates Remained High in 2023: At Least 10 Million Kids in Poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau recently released the updated 2023 measures of poverty: the official poverty measure and the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM).

In 2023, the official poverty threshold was $30,900 for a family of two adults and two children. Families can earn well over this amount and still not make ends meet, especially in high-cost areas. Unlike the official poverty measure, the SPM factors in regional variation in cost of living. For these and the reasons below, the Annie E. Casey Foundation advocates using the SPM.

How Are the Two Measures Different?

- Official poverty measure: Only considers pre-tax cash income and uses national thresholds based on household composition that are inflation-adjusted. Remaining largely unchanged since the 1960s, it offers consistent measurement over time.

- SPM: Considers both cash income and payroll taxes, as well as noncash earnings such as safety net benefits and tax credits, and subtracts necessary expenses (e.g., medical costs). The SPM also uses geographically adjusted poverty thresholds to account for regional variation in cost of living. First released in 2011, this measure improves with new data and methods over time.

By accounting for noncash benefits and tax credits, the SPM allows experts to better assess the effectiveness of interventions to reduce child poverty. Given this and the other SPM strengths noted above, the Annie E. Casey Foundation prefers using this more comprehensive measure of child poverty.

Read more about the differences between the official poverty measure and the SPM.

What Is the Current Child Poverty Rate in the United States?

Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM)

About one in seven (14%) kids are in poverty, according to the 2023 SPM.

The 2023 SPM child poverty rate is up 2 percentage points from 2022 and remains substantially higher than its record low of 5% in 2021. This means that about 10 million kids in 2023 were living in households that did not have enough resources for basic needs such as food, housing and utilities.

See the SPM child poverty rate in your state

The highest rates of poverty generally occur for the youngest children — under age 5 — kids in single-mother families, children of color and kids in immigrant families.

Sign up for newsletters to get the latest data, reports and resources from the Casey Foundation

Official Poverty Measure

The official child poverty rate, which does not take into account families’ non-cash resources and other factors noted above, is higher than the SPM, with 16% of all U.S. children living below the poverty line in 2023. This equates to about 11.4 million kids total. According to the Census Bureau, the official child poverty rate is significantly higher than the rate for the U.S. population as a whole (12.5% in 2023).

In the last decade, the share of children living in poverty peaked at 23% in 2011 and 2012, but has declined since then. In 2022 and 2023, this rate held steady at 16%.

The Effects and Cost of Child Poverty

Growing up in poverty is one of the greatest threats to healthy child development. The effects of economic hardship, particularly deep and persistent poverty, can disrupt children’s cognitive development, physical and mental health, educational success and other aspects of life. These effects reverberate throughout adulthood. Researchers estimate the total U.S. cost of child poverty ranges from $500 billion to $1 trillion per year based on lost productivity and increased health care and other expenditures.

The rise in the SPM child poverty rate in 2023 continues a trend from 2022 in which millions of children fell back into poverty. The health and well-being of these children remains at risk. Now more than ever, as the nation is just recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic crisis, children need security and stability. Decisions by policymakers today will have lasting impacts on young people’s lives — impacts that will affect our country’s future workforce, economy, elections and more.

What Is the Main Cause of Child Poverty?

Child poverty is connected to family poverty. While there is no single cause of poverty, families may fall into financial hardship due to a job loss, expenses that become too high — such as housing, health care and groceries — a transition from a two-parent to a single-parent household or another destabilizing event. Among children and families of color, the picture is further complicated by generations-long inequities and discriminatory policies and practices that have led to income inequality and disparate access to economic opportunities and resources.

Neighborhoods matter, too. Communities with concentrated poverty, which are often racially segregated, tend to have fewer job opportunities for parents and youth, underfunded schools and fewer resources in general. When children grow up in these neighborhoods, it can take generations to move out of poverty.

Additionally, larger economic forces, labor markets and public policies affect child poverty. For instance, parental unemployment and child poverty increase during economic recessions, and labor market factors — such as minimum wage levels — affect poverty rates.

Demographics play a role as well, with older, more educated parents generally able to obtain higher wages. Child poverty rates are also affected by the strength of government safety net programs, such as the extended child tax credit discussed below.

Where Does Child Poverty in America Exist?

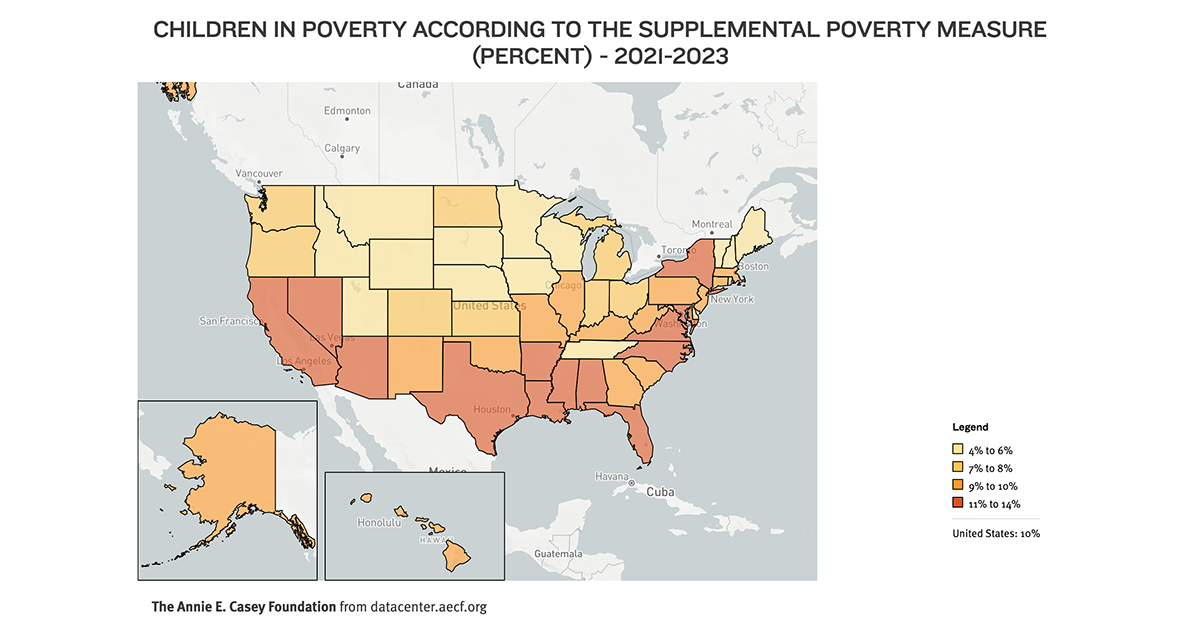

Every state in America has children living in poverty, but higher rates generally exist in the southern region of the country (see map below) as well as in rural areas and urban neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.

- The District of Columbia has the highest SPM child poverty rate in the country, at 15%, followed closely by California, Florida and New York, with 14%, according to 2021–2023 data available in the KIDS COUNT® Data Center.

- Three states share the lowest SPM child poverty rate in the nation, at 4%: Iowa, South Dakota and Nebraska.

- Approximately 8% of kids live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, according to data in the KIDS COUNT®Data Center. Black and American Indian or Alaska Native children are seven times more likely to live in these communities compared to white kids, and Latino children are almost four times more likely.

- About 1 in 4 (25%) children in rural areas live in poverty compared to 1 in 5 (20%) in urban areas, according to a 2022 study.

Poverty in America Disproportionately Affects Children of Color

For decades, children and families of color have borne a disproportionate burden of poverty in the United States, and the latest Census SPM poverty data show a continuation of this sobering trend.

- Latino children: More than 1 in 5 (22%) now live in poverty according to the 2023 SPM, an increase from 20% in 2022.

- Black children: The poverty rate also rose by 2 percentage points for this group, from 18% in 2022 to 20% in 2023.

- Two or more races: The SPM poverty rate inched up from 12% to 13% for these children.

- Asian and Pacific Islander children: The largest increase occurred for this group, with the poverty rate rising from 10% to 14%. However, the category of“Asian and Pacific Islander” represents dozens of highly diverse populations, and disaggregated data from other indicators show that wide socioeconomic disparities persist among these different populations.

- White children: This group has the lowest poverty rate, at 7%, and the rate did not change from 2022 to 2023.

Similar to the SPM, the official child poverty rate reflects persistent inequities for children of color. For instance:

- American Indian or Alaska Native children: The official poverty rate for these children was an alarming 27% in 2023, although it is down slightly from 29% in 2022. (The SPM rate for this population was considered unreliable due to a large margin of error.)

Also see 2023 official child poverty rates on the KIDS COUNT® Data Center by:

- Race and ethnicity for children from birth to age 5

- Race and ethnicity for youth ages 6 to 17

- Child age group

How to Reduce Child Poverty in America

Adequately investing in safety net programs — particularly the expanded child tax credit — is one of the most effective ways to reduce child poverty. According to the Census Bureau, in 2021, expanded tax credits and stimulus payments lifted more than 5 million children out of poverty. That year, the nation was looking at a policy success story: America’s SPM child poverty rate had dropped by half, from 10% in 2020 to a historic low of 5%. The Census Bureau reported that the 2021 expanded child tax credit (CTC) alone removed 2.9 million kids from poverty, one-third of whom were under age 6. The expanded CTC also helped to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in child poverty. These policies clearly worked.

However, the expanded tax credits and payments were temporary pandemic-relief measures, and when they expired in 2022, the number of kids in poverty soared.

Looking Forward: Expand the Child Tax Credit

Important evidence was gathered from the 2021 CTC expansion. In addition to lifting millions of kids out of poverty, this pandemic-era policy corrected a problem in the existing CTC that allowed high-income families to receive the full tax credit while preventing low-income families from receiving the same. In other words, families with the greatest needs received the least assistance. Since the expanded CTC expired, the full credit is no longer available to all low-income families.

Dramatically reducing child poverty in America is an achievable policy goal. Naturally, the temporary pandemic relief measures were not meant to be long-term policies. But now that we know what works to reduce child poverty, lawmakers can move forward with confidence to implement effective, lasting solutions. Strong safety net programs are essential to ensuring that all children have equitable access to the opportunities and resources they need to thrive.

Policymakers should prioritize expanding the child tax credit, strengthening other safety net programs to meet the basic needs of all low-income children and addressing root causes of income inequality and poverty disparities by race.