How Los Angeles County Expanded Youth Diversion

An excerpt from the guide in its colorful, animated style. Image courtesy of the Los Angeles County Division of Youth Diversion and Development.

A new guide from Los Angeles County describes how community outrage over youth incarceration and overcriminalization led activists and practitioners to transform the way the legal system responds to young people in trouble with the law.

Designing Youth Diversion and Development

The guide tells the story of the eventual collaboration among community-based organizations, young people, advocates and public systems on a plan to systematically steer youth in Los Angeles County away from the legal system at the point of arrest — or into community-based services in lieu of formal court processing. It makes the case for dramatically expanding diversion by examining why so many young people were landing in the juvenile system in the first place.

The guide was written with input from young people, community members and advocates, produced by the Los Angeles County Division of Youth Diversion and Development (YDD) and funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

“This guide tells an important, trailblazing story about the capacity of communities and their young people to not only apply pressure as activists but also to be viable partners in the design and implementation of new approaches to juvenile justice reform,” says Jaquita Monroe, Casey Foundation senior associate. “The Casey Foundation supported the chronicling of this story to inspire jurisdictions across the country who may be seeking to significantly expand diversion for young people, and center and uplift youth leadership in the process.”

The guide examines a decade-long push from young people and community groups for collaborative solutions to school truancy, youth incarceration and the overrepresentation of Black and Latino youth among those pushed out of school and into the harshest end of the justice system. The guide describes how this persistent advocacy led to a new approach to reform among local juvenile justice practitioners, community-based organizations and other stakeholders — one that prioritized input from the young people affected by justice system involvement.

What the guide covers

The guide covers:

- how the YDD model came to be and how it works;

- a chronology of what it took to design and implement the approach;

- how communities can invest public dollars to support youth development;

- how to foster collaborative planning and accountability among county partners; and

- ways to center young people affected by the justice system in program and policy design — and how to support their involvement throughout the lengthy, nonlinear process of system reform.

“People shouldn’t just get this opportunity because they happen to live in [Los Angeles] county. Right now, if they live one mile over in any given direction, they could see a different response,” says Refugio Valle, director of the Division of Youth Diversion and Development. But the guide, he adds, offers important insight on how people in other places can get started. “The steps we took might need to look different for your community, but this is how we did it. It’s something that can be done.”

Preserving and empowering youth and community voice

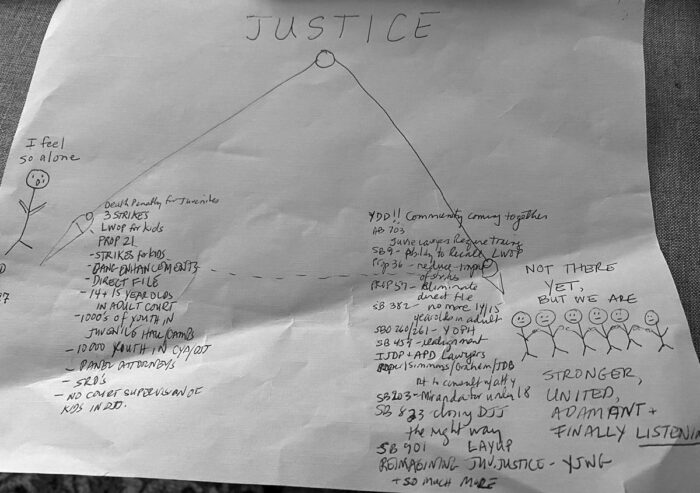

The guide includes quotes, insights and drawings from some of the young people who helped set the vision for and plan the expansion of diversion in the county. Many of those young people have personal involvement with the justice system.

Kent Mendoza, manager of advocacy and community organizing for the Anti-Recidivism Coalition and participant in the YDD development process, affirmed the value that young people who have served time in secure facilities bring to policy or reform discussions. “If we’re trying to talk about undoing any system or anything like that, we have to learn from people who actually lived this experience,” Mendoza says. “They’ve been the closest to the problems and are the closest to the solutions.”

“L.A. County’s story validates community members’ experience with the system as the very expertise necessary to reform it,” says Burgundi Allison, the Foundation’s associate director for diversion and prevention.

What Diversion Looks Like in Los Angeles County

The YDD model works this way: In lieu of arrest, formal filing of a petition in court or even adjudication by a judge, the young person may be referred to community-based organizations by law enforcement, the county district attorney’s office, probation or the courts. YDD identifies these service providers and provides funding, coordination and oversight.

The most common categories of services and activities that youth have asked for so far are school-related support, conflict resolution, recreational and arts activities and work readiness and career development. The organizations are expected to provide programming that speaks to youth, with staff that have similar cultural backgrounds as the young people and are skilled in building trustful relationships with them. Also, the service providers address the harm or trauma that the youths may have experienced in their lives. The length of time a young person spends with the organization depends on the youth’s goals and can be anywhere from three months to a year, with the average length being about six months. They are successful once they substantially complete their goals.

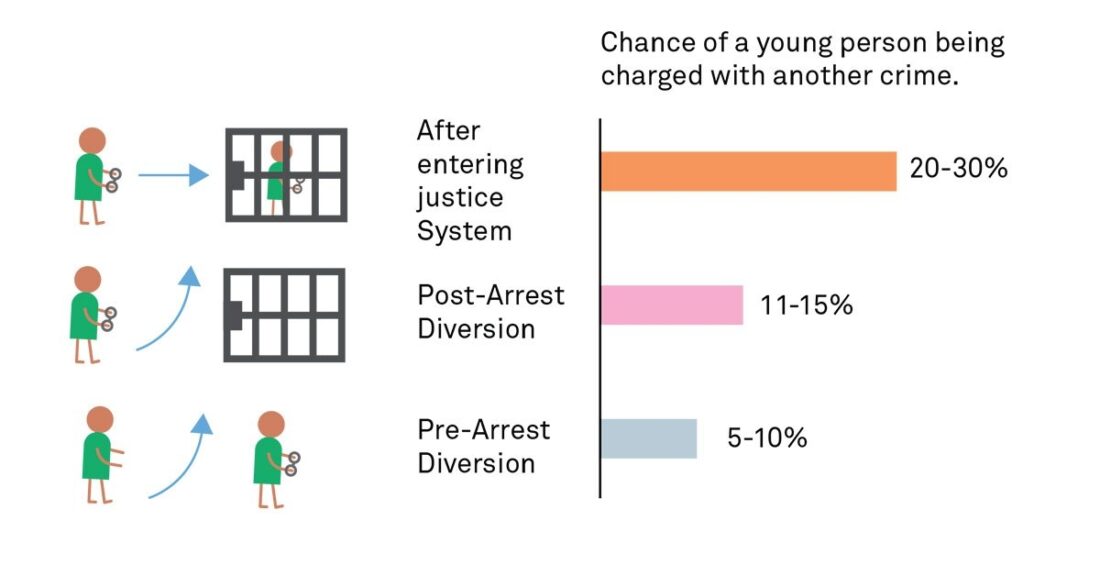

The county’s diversion model is based on evidence that avoiding arrests and formal court processing typically improves youth well-being and leads to fewer harmful outcomes. An illustration in the guide shows youth who are arrested are more likely to be charged again than similar youth who are referred to detention. The chances of a young person being charged with another crime after they are arrested and adjudicated in court are 20% to 30%. That drops to 11% to 15% for youth who are arrested but not formally processed in court and drops further to just 5% to 10% for youth who are diverted by law enforcement before they are arrested.

What Led to Los Angeles County’s Dramatic Expansion of Youth Diversion

A report by the Los Angeles Countywide Criminal Justice Coordination Committee Youth Diversion Subcommittee and the Los Angeles County Chief Executive Office explains that before the 2019 launch of the YDD model, young people in Los Angeles County were drawn into juvenile court systems for infractions as simple and common as being late to class, staying out past curfew or jumping a subway turnstile.

Responses were inequitable: Black and Latino youth were more likely to be arrested and face more punitive consequences than their white peers. Schools around the county had become prime entry points for the juvenile system; Compton and Los Angeles Unified school districts even had their own police departments.

What’s more, without a central definition or oversight structure, attempts at youth diversion were producing uneven results. Young people either were leaving the system without connection to supportive programs or being funneled into boot-camp style programs that have been proven to lead to even deeper involvement in the justice system.