Growing Numbers of Latino and Native Youth in Juvenile Detention Buck Trend

A survey by the Annie E. Casey Foundation of youth justice agencies in 34 states finds that after falling sharply in the early months of the pandemic, the number of young people held in detention centers remained constant between May and August 2020. Even more concerning, the survey finds that the number of Latino and Native American youth in detention centers increased from May to August, reversing some of the gains made in the first months of the pandemic and worsening racial and ethnic disparities.

“It’s alarming that in spite of the risks of COVID-19 and how easily it can spread in detention centers, the population of Latino and Native American young people has actually increased,” says Nate Balis, director of the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group.

While the overall number of young people in detention on August 1, 2020, was 32% below its pre-pandemic level, the population has barely fluctuated since May. The stagnation is happening amid worsening virus indicators in youth detention facilities this summer, leaving thousands of confined young people without access to opportunities or connections and increasingly vulnerable to the virus.

“The additional risk of transmission of COVID-19 should make safely shrinking the population the priority for youth justice systems when it comes to their use of secure detention,” Balis says. “Simply maintaining the population ignores increasing evidence of the virus in youth detention facilities, despite the precautions many have taken.”

Key Findings From the Juvenile Justice Survey

These trends are reflected in an Annie E. Casey Foundation survey of jurisdictions around the country aimed at assessing the effects of the pandemic on juvenile justice systems through August 1, 2020.

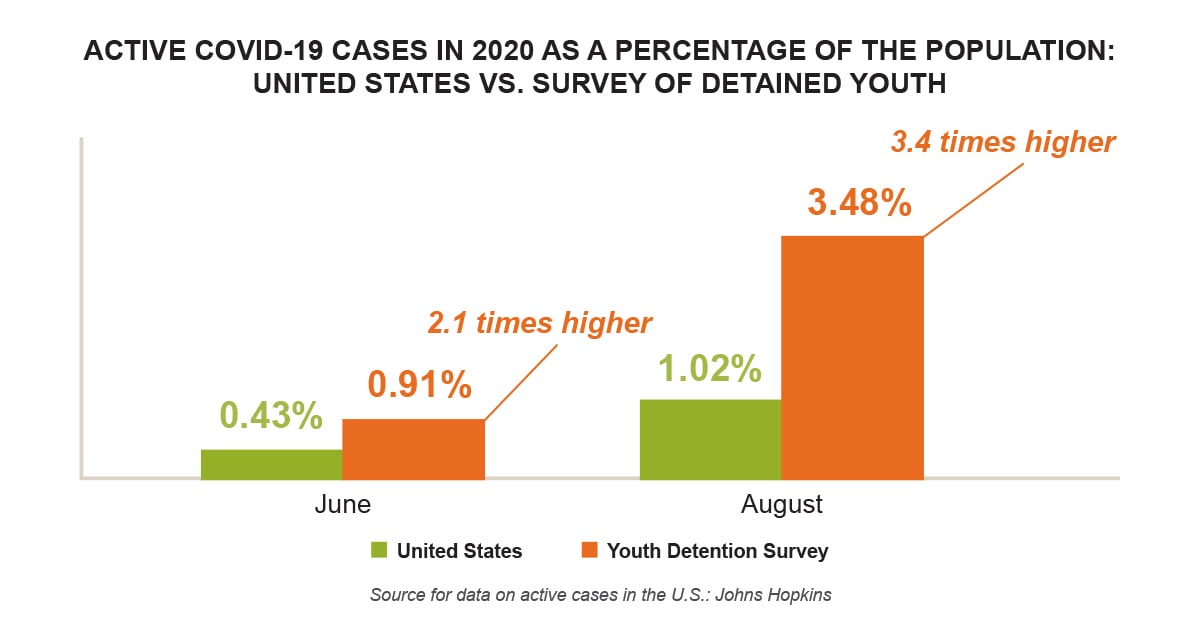

COVID-19 was more prevalent across detention facilities in August than in prior months.

At the time of the survey, jurisdictions reported 103 young people and 172 staff members who were confirmed or suspected to have COVID-19. The number of youth cases in August was the highest reported in this survey to date. The prevalence of active COVID-19 cases among youth in detention in August was three and a half times higher than for the United States population as a whole.

The number of jurisdictions with cases increased and so did the likelihood that a young person in detention was in a jurisdiction with one or more active cases. Forty-one percent of all youth in detention as of August 1 were in jurisdictions reporting active COVID-19 cases among youth and/or staff — an exposure rate almost doubling the 24% initial peak in May. The American Academy of Pediatrics cites a “grave risk of devastating consequences from the coronavirus” for youth in the justice system.

Despite greater incidence of COVID-19 in secure detention, admissions have risen, and the population has been flat since May.

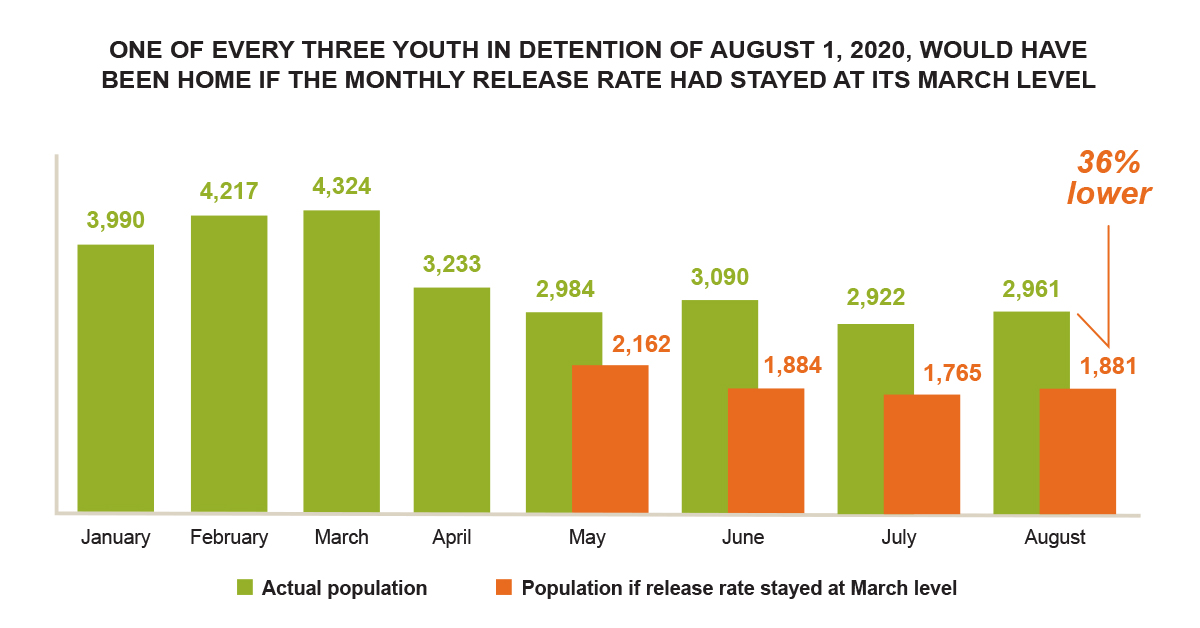

June and July saw small rises in admissions per day, offset by some modest acceleration in the pace of releases. As a result, the population of detained youth held steady. The release rate is the percentage of all young people in detention at any point during a month who were released before the end of that month. On average, the higher the release rate, the shorter the stays in detention.

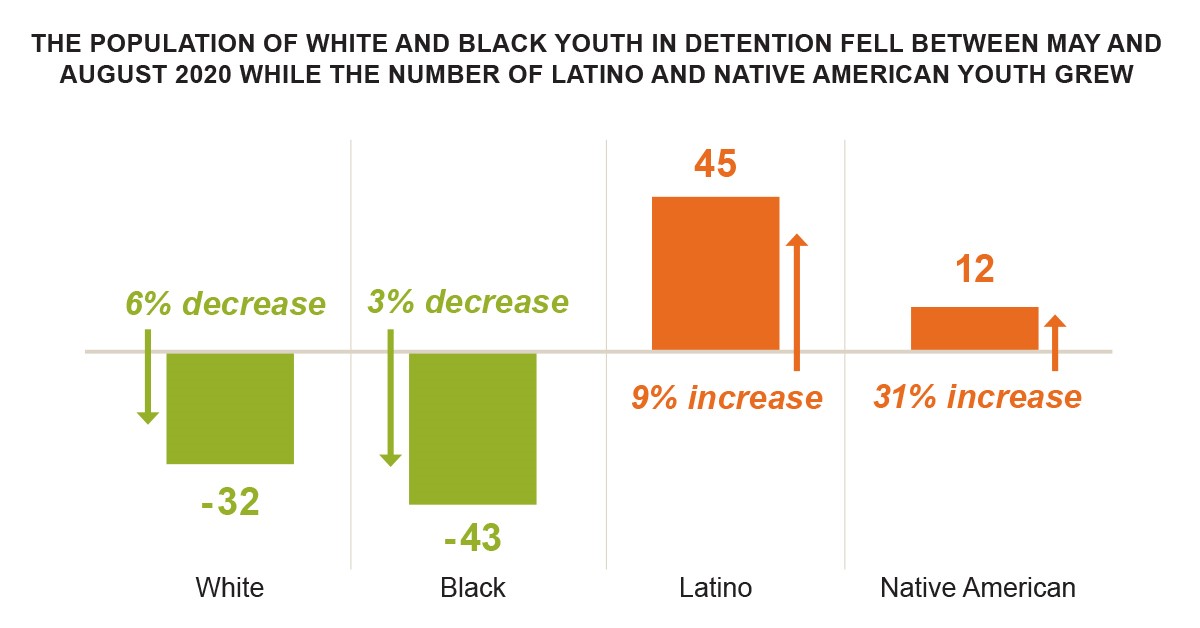

Disparities that disadvantage Latino and Native American youth compared to white youth grew from May to August.

In June and July, among jurisdictions that provided information disaggregated by race and ethnicity, white youth continued to be released from detention faster than youth of color. The gap favoring white youth has grown since before the pandemic began in February, particularly compared with Latino and Native American youth. In July, the release rate was 61% among white youth compared with 55% among Black youth. The rate was 52% for Latino youth and worse still among Native American youth (50%).

At the same time, disparities in admissions have increasingly disadvantaged youth of color, especially Latino youth. The rate of admissions per day, after falling by roughly half for all groups in the first two months of the pandemic, ticked up by 10% among white youth from April to July. It increased among Black youth by 20% and surged among Latino youth by 28%.

Faring worse in both release rate and admissions, the detained population actually increased between May 1 and August 1 among Latino youth (9% increase) and Native American youth (31% increase), reversing much of the decrease in detention among these groups between March 1 and May 1. The detained population of all other youth declined by 4% during that time.

One of every three youth in detention on August 1, 2020, would not have been in detention if the release rate had stayed at its March level.

Had the release rate in June and July stayed at the March rate of 65%, then far fewer young people would have been held in detention on August 1, 2020. The actual population as of August 1 was 2,961. It would have been more than one-third lower, just 1,881, if the March rate were maintained. Among jurisdictions that provided information disaggregated by race and ethnicity, if all youth had been released in every post-pandemic month as quickly as white youth were released in March, then the population would have been 38% lower for white youth and 52% lower for non-white youth.

The Role of Detention Centers in Juvenile Justice

Detention centers are different than youth prisons or other residential placements where young people could be sentenced after being adjudicated delinquent. Rather, detention is a crucial early phase in the juvenile justice process. It’s the point when the courts decide whether to confine a young person pending their court hearing or while awaiting placement into a correctional or treatment facility rather than allowing the young person to remain at home. Every year, an estimated 195,000 young people spend time in detention facilities nationwide, despite the negative effects of detention on young people and persistent racial disparities in who is detained.

About the Survey

Working with the Pretrial Justice Institute and Empact Solutions, the Foundation first collected data just weeks after the coronavirus arrived in the United States.

The jurisdictions responding to the latest survey are home to 30% of the U.S. youth population, ages 10 to 17. Most of the responding communities are involved in the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative® (JDAI®), a network of juvenile justice practitioners and other system stakeholders across the country working to build a better and more equitable youth justice system.

This survey, conducted from August 5 to 26 and covering the period from January 1 to August 1, is unique because it reports on data from hundreds of jurisdictions in close to real time. Information came from large urban counties and small rural courts, among a wide range of jurisdictions that collectively held 4,324 young people in secure detention on March 1, 2020. For perspective, approximately 15,660 young people were held in detention nationally on any given night, according to the most recent federal data from 2017.

There are no direct points of comparison that place these data in context. Available data on detention utilization from national surveys indicate that significant changes in detention typically accrue over several years. The data are self-reported, and we cannot independently vouch for their accuracy.

This is a non-random sample, so it is not an accurate source from which to derive national estimates nor determine statistically how representative this group of jurisdictions is of the nation as a whole. While there is overlap, the pool of jurisdictions replying to a monthly survey is unique to that survey alone, so monthly results cannot be directly compared.

Find a set of questions that can help juvenile justice leaders reduce youth detention