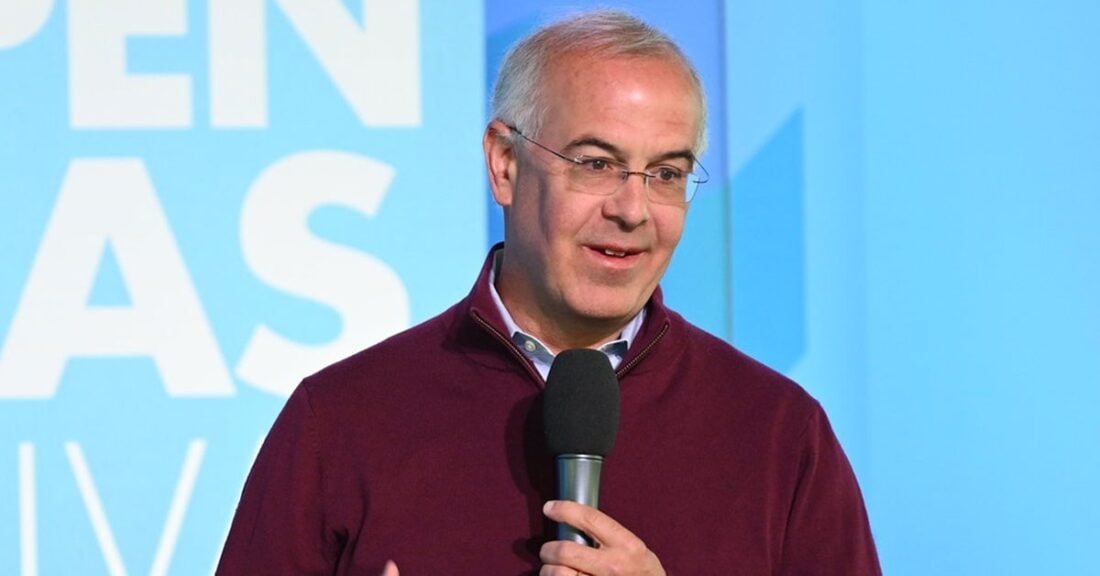

David Brooks on Being Seen, Social Trust and Building Relationships

David Brooks is a best-selling author, sought-after scholar and longtime columnist for the New York Times who writes about politics, culture and the social sciences.

In 2018, Brooks added another title to his resume: Founder of Weave: The Social Fabric Project. An effort of the nonprofit Aspen Institute, Weave aims to counter the rising tides of individualism, cynicism and incivility in modern society. It does this by elevating the efforts of Weavers — everyday Americans who show up for others, lead with love, invest in relationships and, along the way, transform their communities and their lives.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Lisa Hamilton recently spoke with Brooks about his work and the launch of Weave. Their conversation examines some of the key forces — from policymakers and Weavers to technology and the COVID-19 pandemic — that are impacting social trust, social interactions and the social fabric of America today.

A big thank you to Brooks for chatting with us!

Stream this CaseyCast episode on building stronger communities

Subscribe to CaseyCast on your favorite podcast service:

In this episode on community building, you’ll learn

- The goals of Weave.

- How technology does — and doesn’t — support stronger social connections.

- How the pandemic has influenced Weave and its work.

- How policymakers can support equitable opportunities for kids and families.

- What traits Weavers have in common.

- Examples of Weavers in action.

Conversation clips

In Brooks’ own words…

“We just wanted to tell their stories, to celebrate them, and maybe inspire people to live a little more like them.”

“A culture of hyper-individualism, where people see their life as an individual journey, is going to be a culture with a lot of detachment and distrust.”

“The crucial skill, in the center of any healthy community, is the ability to see each other well and to make others feel seen and understood.”

“As people, we’re built for deep communication over time with the same few people.”

“I’ve really come to believe that people in the community know how to fix their problems. They just need the right resources and support.”

Resources and links

- Lisa Hamilton on Twitter

- David Brooks on Twitter

- Weave: The Social Fabric Project

- Robert Putnam

- Resident Association for Greater Englewood (R.A.G.E.)

- LB Prevette

- Samuel Huntington

- The Second Mountain

About the Podcast

CaseyCast is a podcast produced by the Casey Foundation and hosted by its President and CEO Lisa Hamilton. Each episode features Hamilton talking with a new expert about how we can build a brighter future for kids, families and communities.

Enjoy the Episode?

We hope so! Visit Apple Podcasts to subscribe to the series or leave a rating or review.

Lisa Hamilton:

From the Annie E. Casey Foundation, I'm Lisa Hamilton… and this is CaseyCast.

Joining us today is journalist David Brooks. David is a best-selling author and Op-Ed columnist who has covered politics, culture and the social sciences for The New York Times since 2003. Among his many other roles, he has served as a reporter and Op-Ed editor for The Wall Street Journal, senior editor at the Weekly Standard, contributing editor at Newsweek and the Atlantic, and commentator on NPR and the PBS NewsHour.

In 2018, David added another assignment to his plate, when the Aspen Institute, a D.C.-based think tank, tapped him to launch a community building initiative called Weave. The project aims to build social trust, to address the root cultural cause behind many of America's social problems.

Now David, I realized I haven't covered all of your career highlights, but for the sake of giving us more time to talk, welcome, and thank you for joining us on CaseyCast.

David Brooks:

It's a great pleasure to be with you, Lisa. I'm a big fan of the Foundation, so it's, I feel at home here.

Lisa Hamilton:

Well, thank you.

Well, at the Casey Foundation, we talk a lot about what it means to build strong communities and the role that they play in supporting families and kids. Based on all the journalism you've done through the years, I'm sure you got a perspective on this topic. So, from your vantage point, what do you think makes a strong community?

David Brooks:

Well, let's start at the root. If you go back to the Bible, you got — in the book of Exodus — it's really a book about forming community, and one of it is, one of the basis is it's a story, it's a group of people… who are enmeshed in a common story and so the book of Exodus happens in order to be retold and that story is retold year after year and Jews live out that story. The second thing and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks pointed this out once, that in the book of Genesis, the creation of the universe is covered in like nine verses.

In the book of Exodus, the creation of the building of the tabernacle, it takes like 300 verses and they repeat it, repeat and repeat. And why is that? It's because a community is a group of people with a common project. So a common story and a common project, and that gets people working together and having to see each other, and I think that's part of the basis of community.

Lisa Hamilton:

Hmm, I love that idea because the stories we tell ourselves can definitely define the way we see ourselves in, in community with others.

You have written before about watching America's social fabric decay. Say more about what this means and how you think it plays out compared to your definition of what community is about.

David Brooks:

Sure. Well, a community is also built on trust and trust is the expectation that you're going to do what you ought to do. That we have the same set of values and that we understand what the right thing to do, that we have a set of norms. So, if we're merging traffic between two lanes, one lane goes and then the other lane goes, and if you butt-in line, I'm going to honk at you, because I want to keep up the norms.

And, unfortunately in America, our trust levels have just, just declined, precipitously. If you asked people two generations ago, "Do you trust the institutions of society?" 70% or 80% said, yeah, I do, and now it's down to about 18%. Worse, if you ask people two generations ago, "Do you trust the people around you?" 60% would say yes. Now it's down to 33%. And the younger the person is, the more distrust they have, and only 18% of young adults say they trust the people that were around them over 70% of young adults say most people are out or selfish out for themselves.

And younger people are distrusting because the world has been untrustworthy, and their distrust is an earned distrust. And so, a lot of people feel that they live in a society where they can't trust the people around them. They don't have a sense of existential safety.

And I think that causes a lot of political polarization. I think it causes opiate addiction. It causes people in communities not to do what this social scientist calls “spontaneous sociability.” That if we have a problem, of course, we're going to get it out of our house and help each other solve the problem, and so people tend to withdraw. And so, I think that this distrust, is it at the source of a lot of our different problems.

Lisa Hamilton:

Can you name an event or a set of circumstances that you think led to this distrust? Or do you think it's something that's just built over time and are there factors that are even contributing to having people tell this story of distrust between themselves and others?

David Brooks:

Yeah, well, for the distrusted institutions, there was a clear inflection point and that was the time of Vietnam and Watergate. We really began to slide and then, trust went up a bit in the 90s and then went down and it's been down pretty much ever since recently. Distrust in each other is… is more a cultural thing in my view.

It's, we had a culture, as Robert Putnam, the Harvard, sociopolitical scientist says: "We had a culture of ‘we’ in this country", and that maybe I didn't have as much personal freedom, but I was committed to a place and to a "we." And, if like, if you're from Chicago in the 50s, you didn't say I'm from Chicago.

You said I'm from 59th and Pulaski, because that neighborhood was your, it was your place, and you may have joined the same union your dad did or mom did, and you lived there.

But the pro… and those were tight communities in the 50s in Chicago. The problem was they were racist; they were sexist; they were anti-Semitic; they were communities built around limitation. And so we wanted to get rid of limitations and we adopted a much more individualistic culture and we obviously needed to do that. But I think we've overshot the mark and a culture of hyper-individualism, where people see their life as an individual journey, is going to be a culture with a lot of detachment and distrust.

Lisa Hamilton:

Hmm. Well, that, I'm sure, led to your role in helping to launch Weave at the Aspen Institute. Say more, tell us about the project, why you thought it was needed and what its aspirations were.

David Brooks:

Yeah, if community is falling apart, if trust is declining, it's this problem is being solved on the local level, by people we call Weavers. And people who are Weavers tend to work in the neighborhoods where they live. An example is… to stay in Chicago with, we met a woman named Keisha Butler, who was living in Englewood, which is sort of a tough neighborhood in Chicago. And she was going to move out. And as she was about to move out, because it was violent, she looked across the street and saw a little girl playing in an empty lot with broken bottles. And she turns to her husband and says, “I'm just going to… not going to be another person to leave this. We have to commit to this neighborhood.” And so, she sent away the moving vans, and she joined some volunteer organizations, she got involved one way after another, and now she runs Rage, which is the big community organization in Englewood. And these people are, are everywhere.

We would go to the country, McCook, Nebraska, a little town there, or Wilkesboro, North Carolina or New Orleans, or you know, big cities. And you just ask, "Who is trusted here?" And there are people serving communities, either through organizations or just spontaneously. And they say, “Oh, that person is trusted here.” And so, we just wanted to tell their stories, to celebrate them, maybe inspire people to become, live a little more like them.

Lisa Hamilton:

Hmm. Anything that you saw in common with these Weavers?

David Brooks:

Oh yeah, a bunch of stuff. They first, they had a, what I call vocational certitude. They never said, "I'm going to do this for a few years now, go off and do something else." They knew why God had put them on this earth. They had, they were, were motivated by moral values. They wanted to live in right relationship with others. They tended to be really good at being with other people and building relationships, and a real love of a place… That I met a guy in Youngstown, Ohio, who just started his work by standing in the town square with a sign that said, "Defend Youngstown." And they just, there's a certain love of a place and they want to, they want to serve it.

And I think one of the things that frustrates them as people from outside their neighborhoods come in, sometimes they get a foundation grant, and they stay three years and then they leave and they never really build up trust in the community, they don't know the community. And I've really come to believe that people in the community know how to fix their problems.

They just need the right, right resources or support. They understand their, their problems.

That the neighborhood is the unit of change, don't try to fix one person. And that does good if you lift one person up, but usually, as a friend of mine says "You can't only clean the part of the swimming pool you're swimming in." Thinking about transforming neighborhoods is the key way to think about this.

Lisa Hamilton:

Right, yeah, water, water moves. You can't really contain it, so that's a great way of thinking about it, the container of, of change. I think that's wonderful. And I guess just, that, it, can you tell me what the goal of the project is? Have you brought these Weavers together?

David Brooks:

Back before COVID, we would get them invites to South by Southwest or on the radio, so they could talk about their work. One of the more rewarding things is we, before COVID again, we brought them before high school audiences, and so there's a woman named L.B. Prevette, who does counseling with LGBTQ kids in rural North Carolina. We, just to watch her describe her work before an audience of high school kids was, you know, that's, that was fun.

Lisa Hamilton:

Oh, that's beautiful. Well, it, you know, I know when we first began there wasn't a pandemic, but COVID-19 hit and one of our solutions, as a society, was to practice social isolation, and so I'm wondering how the pandemic has affected the role and urgency of Weaves work.

David Brooks:

I think increased the urgency because we've seen a rise in suicides and a rise in depression and a rise of stress. So, the social fabric is an ever more fragile state.

I would say a lot of the Weavers, we got to know and really admire, in the beginning, I remember the first weeks one of them said to me, “I was born for this.” And she and her organization, which is mostly an organization that helps underperforming kids in Baltimore, they created a fast network of food distribution, and so she pivoted, and she stayed active, but then her community had new needs. She, and the other people that she'd met in, in Baltimore were used to working together on things. So, they were readily able to pivot over and suddenly become a food distribution network, and they could buy large quantities of food at reduced rates.

So, I think it's, some of them, people have lifted, have really shifted and really served their communities in new ways. For our work, I would say it's been hard, because we're really about bringing people and it's been hard to do that over Zoom. We do, you know, we try, but it's a challenge.

Lisa Hamilton:

I think you're right, we, we have seen just amazing acts of generosity spontaneously around the country.

So, while we're on the topic for anyone who's studied social change, 2020 was likely a very interesting year. What did the year teach you about how social change works or doesn't work in America today?

David Brooks:

Well, I was, I was really informed by a book from the late political scientists, Samuel Huntington, who said about every 60 years, America goes through a moral convulsion, that you get a new generation arising on the scene. People become disgusted with established power. There's usually a new communications technology, people want change. He said, this happened in the 1770s with the revolutionary period, in the 1830s with the Andrew Jackson period, the 1890s with the progressive era and then the 1960s. And in around 1981, he said, yeah, if the pattern holds, maybe there'll be another period of moral convulsion around 2020. So, he was right.

So, to me, it started in 2014. It started with the rise of the populous movements around the world. Simultaneously the rise of Black Lives Matter and Ferguson and all that, and then other things, social movements arising. And so, then Trump was elected, and so we were in the convulsion, and to me, 2020 was like a hurricane in the middle of an earthquake, and so we had a lot.

I think the comforting thing is, you come out of them, these periods of time, or when you're in the middle of it, it can feel like everything's falling apart. But people adapt and change and come out, when you come out, the culture's different, people look at things differently. So, in the way, 1965 was very different from 1975. You look at the high school yearbooks in '65 or everybody has, all the guys at least have short hair, and by '75, they all had long hair and different attitudes. So, I, I'm hopeful that we're coming out with it with a different set of attitudes.

Lisa Hamilton:

So, let's talk about young people today. They are digital natives. They have never known life without technology at their fingertips, but instant access to others and to information and answers, hasn't spared them from feeling lonely as you pointed out. What role does technology play in building stronger connections and communities, and in what ways does it fall short?

David Brooks:

Well, we have to be careful about it. I, you know, I think in many ways, it, it has fallen short for many ways, because we're not used to shallow communication, where as people, we're, we're built for deep communication over time with the same few people. This allows shallow communication, often comparative with a wide variety of people, many of whom you don't really know. So it's a form of knowing that's not knowing it. There's a form of judgment, but no understanding. And it's, it's very competitive and comparative. So, I think it has imposed a strain on people of all ages. I know my attention span is not what it was because of the phones.

Nonetheless, I think it's a tool we can learn to use when you get a new technology, it takes a while to realize the upside and avoid the downside. So, I have a friend who he gets up every morning and before he looks at a screen, he goes outside and looks at the sky just to orient himself in the real world. And, I assume younger generation will learn it just as well, maybe ahead of the rest of us.

Lisa Hamilton:

Right, and that it's not a replacement for human connection, but maybe additive in some ways to the real meaningful engagement that we all need with one another, so I think that's a valuable point. It's not in and of itself bad, but it's, when we allow it to play too large of a role or in place of a human connection, it can certainly have lots of downsides.

Well, let's talk about what it looks like in everyday life to prioritize connections with others. In what ways might we promote that, and, and in other ways, how might we be creating greater disconnection in our daily lives, maybe beyond the technology aspects of it?

David Brooks:

Yeah. Well, you know, one of the things I'm working on now is, is how we see each other. Because it seems to me the crucial skill in the center of any healthy community is the ability to see each other well, make them feel seen and understood. There's nothing more alienating when somebody doesn't see you. So, I'm spending a lot of time, like, what is this skill? I think it involves first, just a loving attention on the other person. You're not casting a detached cold attention, and second, it’s a, it’s a process of accompaniment when you're, you're living their lives with you. As you live, you begin to observe each other and you get a feel for how each other feels, how they respond. Seeing someone's not knowing the facts about someone, it's knowing how they perceive the world. In order to be known, you have to know how they know you.

Then finally there's empathy, but empathy is, is good, but not enough. You have to ask questions to really know someone. You just have to ask them questions, because they can tell you. So those are questions, like, what crossroads are you at? That's a question about what stage in life they are. Who were you in high school? And how has that changed? That's a question about social location, you know, were you an insider or were you sort of an outsider? All sorts of things, I mean, one question that's a serious, don't ask this at first, but like, how do the dead show up in your life? We all have family legacies and heritages that show up in our lives and how we see the world. And so, I'm a big believer in dual attention that we, we sit together, and we talk about each other and then we, we really come to see each other, and I think that's the really the foundational building block of connection.

Lisa Hamilton:

Hmm. Oh, I love that. And, and to allow others to belong, part of the work we've been doing recently is exploring this idea of belonging. How do people feel like they are welcome in a space? And I think many of the things you suggested about, I'm just trying to get to know people and seeing them authentically, seeing them for who they are, is so critical to helping anyone. So I, I think that is a great, great advice.

You know, building connections with others takes time, but so many of us are struggling with what's already on our plate. There's always too much to do in one day, and community building can feel like a luxury, though you've highlighted individuals who have made it a priority in their lives. Talk about why any of us should make community building a priority beyond the Weavers who do it on an extraordinary level.

David Brooks:

They often do it almost professionally, you know, they've run an organization, stuff like that. But you know, a lot of people just, invite their neighbors around for dinner. I have a friend who says she practices aggressive friendship. She's the person who offers the invitation. You know, you can just do a small act of service.

We ran into a lady in Florida just helps the elementary school kids across the street after school. If she's not a paid patrol person, she just does it. And we asked her, "Do you have time to volunteer in your community?" And she said, "No," I have no time, and well we said, are you getting paid? She said, "No."

Lisa Hamilton:

She's doing it.

David Brooks:

She just doesn't see it as volunteering. She sees it, it's just what neighbors do.

Lisa Hamilton:

Another topic you've written about, and that's a key focal point for Casey, is inequity, and that certainly plays into how communities feel. What role do you see policymakers playing in leveling the playing field for America’s kids and families?

David Brooks:

Well, I mean, if you, I told, I could tell many stories, I've already told a couple of stories about America in the last 50 years, but another one is that we have funneled large amounts of money to college-educated people, often seniors, who live in and around big cities. That if you fill in that category, high education level, big city, you're probably seeing your home values go up, all sorts of things, and older. We've not done so well with less-educated people, people with less education levels, and with kids. We've spent a lot of money on health care for affluent seniors, not enough on kids.

So, just in terms of policymaking, if I could get political for a second or governmental anyway, you know, the, the agenda that Joe Biden has thrown out there, both in his infrastructure plan and in his family plan is a big funnel of money to people with lower education levels and kids. So I'm very excited about the child tax credit. I'm very excited about pre-K. That's a big deal. So, I, you know, we've, we've just under invested in children for a long time and you guys have filled in the gap as much as you can, but the scale of government is just big. So, I-

Lisa Hamilton:

It is.

David Brooks:

do think there are, there are ways policymakers can really help you.

Lisa Hamilton:

I, I totally concur. It is exciting to see children and low-income families on the national agenda, and to hear people talking about child poverty, it is just the biggest travesty in our country to allow so many children to grow up disadvantaged, and it is to all of our disadvantage having done that. So, I, I like you and I'm excited to see our country talking about what we can do to help more children have thriving lives.

Well, we've talked about Weave a bit, but you also are a successful author and your, your latest book is called The Second Mountain, and explores what it means and what it takes to live a meaningful life. Say more about The Second Mountain. I've heard you talk about this in person, but I'd love for our listeners to hear about this journey and what you think it means.

David Brooks:

Yeah, it was, my view was that, for most of us, we get out of school, and we have a mountain we want to climb, which is often involved some career success or making an impact on the world and establishing identity. Then lo and behold, at some point in life, for most of us, either you fail or something bad happens, or,

Lisa Hamilton:

Or you made it!

David Brooks:

or you make success, you achieve success, but it's less satisfying than you thought it would be. Or something bad happens that wasn't part of the original plan, like a cancer scare or something. So, you spend a period in the valley, and the period in the valley is no fun, but it does tend to knock your ego around and diminish your ego. So, a lot of people, including myself, have a life shape where you spend some time in the valley and then, but then in the valley you realize, oh wait, there's a second bigger mountain for me to climb, which is this mountain of, of, of generativity, it's less about ego, it's more about relationship or things like that. I find a lot of people who have had this life shape, so the book is really about a lot of different people, who've, who've spent some time in the valley and, and really discovered a larger purpose.

Lisa Hamilton:

Mm-hmm, and I imagine many of them end up being Weavers in their community in some way or another, that they find greater satisfaction in helping others beyond the sort of self-driven motivations of earlier careers.

David Brooks:

Yeah, no, I have run into a guy who wanted to become an entrepreneur. He said, I'm going to become a successful entrepreneur and retire at 40 and then spend the rest of my life doing good stuff. And he made enough money somehow to, I think it's solar panels or something to, to retire five days before his 40th birthday, and he went back to his school in Ohio, it was a little school and he sent everybody to college for free. So that's not a normal story that we don't all get to retire before age 40, but, but it's a story.

Lisa Hamilton:

Aww, that's great. Well, I guess I'm in my part of my second mountain, I was a corporate executive for 14 years, and now I've been 10 years at Casey and using all those corporate skills in service of kids and families. I'll tell you, it has been extraordinarily rewarding, so maybe we can find the third mountain.

Well, that it's, it's great to hear what you've been writing about is there something you're tackling next, what's your next topic?

David Brooks:

Well, as I mentioned, I'm writing about seeing and being seen that's my next topic. And I can get to go back to teaching a little again. So, I love teaching. It's one of the disadvantages of being a newspaper columnist and writers. You don't get to see your audience. You're like, send it out there, but in the classroom, you get to see the same faces and you get to know the names. So, I, I, I like teaching for that purpose.

Lisa Hamilton:

Oh, that's great. Well, I look forward to reading your next book and hearing about all the things there are to learn about how we can build more inclusive communities, where everybody feels like they are seen and appreciated, that sounds like a great next topic.

Well, I want to thank you for joining us on CaseyCast and for sharing your work with us and to our listeners. Thank you for joining us today.

You can ask questions and leave us feedback on Twitter, by using the CaseyCast hashtag. Also feel free to follow me at LHamilton_AECF.

To learn more about Casey and the work of our guests, you can find our show notes at AECF.org/podcast.

Until next time I wish all of America's kids — and all of you — a bright future.