Five Questions with Casey: Bart Lubow and Reducing Reliance on Youth Detention

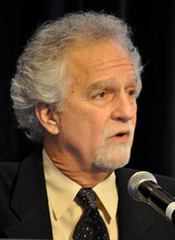

For more than 20 years, Bart Lubow has led the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), an ambitious effort to demonstrate that jurisdictions can reduce reliance on secure detention without sacrificing public safety.

For more than 20 years, Bart Lubow has led the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), an ambitious effort to demonstrate that jurisdictions can reduce reliance on secure detention without sacrificing public safety.

As director of Casey’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group, Lubow also guides efforts to improve outcomes for young people who enter the juvenile justice system and to reduce disparities in the treatment of young people of color.

Lubow began his career in criminal justice as a social worker for New York City’s Legal Aid Society and served as director of Alternatives to Incarceration for New York State before joining the Foundation in 1992.

Q1. The Foundation recently reported that youth confinement is at an all-time low. Were you surprised by this trend in recent years?

We knew that sites involved in JDAI were dramatically reducing their reliance on detention and placements in correctional facilities. We also knew through Casey’s strategic consulting work that a number of other states have reduced their numbers of confined youth as well. While we weren’t surprised by the overall numbers nationally, we were very pleased to see that the trend is almost universal across the country, with 44 states reporting substantial decreases in youth confinement.

Q2. Why do you think the incarceration rate for youth has dropped, and what’s the significance?

The reductions reflect a convergence of factors. First, we have learned a lot over the past two decades about what does and doesn’t work to change juvenile behavior. The research shows that putting kids into detention increases the risks of recidivism at a huge cost to taxpayers. Similarly, we have learned that adolescents don’t think like adults, so some of the basic punitive notions upon which juvenile incarceration is based don’t actually make sense. When you place low-risk populations with high-risk populations, the former typically come out with a greater chance of recidivism.

Second, Casey is seeing a vibrant movement to reduce reliance on incarceration, in part due to JDAI and some state-specific reform endeavors. Jurisdictions of all political shapes and sizes are challenging the system’s reliance on confinement and promoting best practices to end it.

Fiscal hard times also have been a catalyst, since the lion’s share of funding for juvenile justice comes from state and local governments that have been struggling mightily since the recession.

Finally, there is no doubt that the sustained decrease in juvenile crime over the past 15 years has created space for more rational discussion about what’s smart on crime rather than tough. The numbers dispel the myth that locking up fewer kids would unleash a juvenile crime wave.

Q3. What are some essential factors in safely reducing reliance on juvenile detention and incarceration, and who is doing a good job?

Changing the values, policies and practices underlying the system is the key. You can’t append good programs to ineffective systems and expect to get different outcomes. If you don’t have systemic policies and practices aligned with new programs, you won’t do a good job of identifying the young people who would have been incarcerated. It’s not just about funding more alternative programs; you don’t want to fill these programs with kids who wouldn’t have gone on to incarceration anyway.

Q4. What are some places that have adopted these kinds of approaches?

Many local sites participating in JDAI are doing this well. They focus—first and foremost—on changing the behavior of the adults who work in and manage the system, which results in important shifts in values, policies and practices. At the state level, Ohio and Connecticut are good examples of what this type of change looks like. Ohio has provided fiscal incentives for county courts to keep kids at home or in local programs, so they radically reduced the numbers in state confinement. Connecticut implemented evidence-based programs that have produced better results in terms of recidivism and adolescent risk-taking behavior. As a result, incarceration rates and juvenile offending rates have gone down.

Q5. How can we address ongoing disparities in how youth of color are treated by the juvenile justice system?

We must ensure that systems provide a level playing field in which all kids are treated equally, regardless of race or ethnicity, and that they can respond to the particular needs and circumstances of the young people who come to them. Juvenile justice systems need to be more intentional about efforts to dig deeply and root out the sources of disparate treatment. They need to do a much better job of engaging community organizations and the youth and families involved in the system.

Jurisdictions serious about reform must first collect data to describe who they are confining, why they are being confined and their outcomes. Stakeholders need to talk about what confinement is being used for and whether it is accomplishing its intended goal. Most important, systems must treat kids who come to court the way we would want our own children to be treated.