Report Explores How Adolescents Leave Foster Care

A new study funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation examines the reasons that teenagers exit out-of-home care and the variables influencing their path.

The report, by the Center for State Child Welfare Data, is based on a review of child welfare placement records for approximately 55,000 adolescents nationwide. It focuses on young people who entered foster care in their teens and analyzes the three main reasons why they leave. “Understanding these differences,” write the Center’s researchers, “is one key to developing smart child welfare policies.

The top three exit reasons identified by the study, Understanding the Differences in How Adolescents Leave Foster Care, are:

- achieving permanency through adoption, guardianship or reunification with birth parents (61%);

- aging out of foster care (14%); and

- running away (13%).

These three categories are influenced by child characteristics (age, race/ethnicity and gender), placement history (type of care and number of moves) and county characteristics (socioeconomic status and urbanicity), according to the study.

“These findings can inform how we approach systems reform around older youth in care to increase the likelihood that they leave foster care with a permanent family,” says Jeff Poirier, a senior associate with the Foundation’s Research, Evaluation and Data team, which works closely with Casey’s Child Welfare Strategy Group and Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative. “Significantly, it also raises questions about why young people run away from care at high rates, which research should further explore.”

Other key findings shared in the report include:

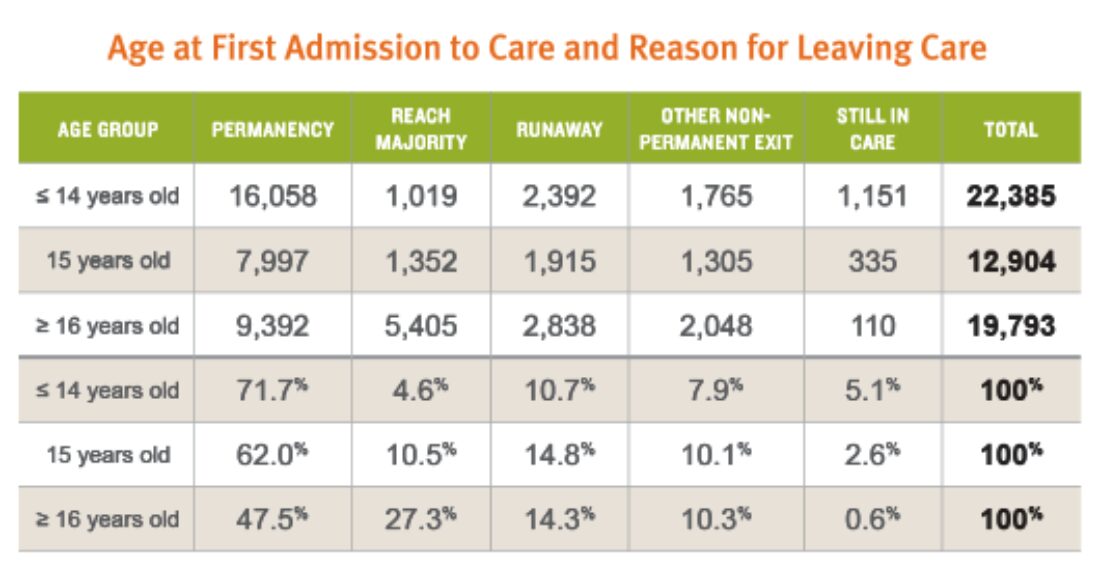

- As the age at admission to foster care rises, so does the probability a young person will run away.

- Young women are more likely to run away from care, while young men are more likely to age out of foster care.

- Black youth are less likely to join a permanent family than white or Hispanic youth. Black and Hispanic youth are more likely to run away from care but less likely to age out of care.

- Teenagers who spent 90% of more of their time in kinship care have the highest permanency rates.

The report pays particular attention to adolescents who run away, do not return to care and whose outcomes are completely unknown. This scenario, while alarming, has received little attention. For example: Reporting of runaways is inconsistent across states, and the U.S. Department of Health Human Services does not use running away as a metric when tracking the performance of state child welfare systems.

In addition to recognizing adolescence as a unique period of development, the study emphasizes the heterogeneity of the teenage years. Exit reasons for young people who enter care at ages 13 and 15 are “markedly different,” the report’s authors write, adding that their findings “highlight the importance of understanding placement outcomes from a developmental standpoint. These baseline differences must be accounted for when planning service improvements.”

More broadly speaking, the report serves us an important reminder for those working in the child welfare field. “These data show how important it is that child welfare systems never give up in trying to find a permanent family for teenagers, and how important it is that teenagers live in families if at all possible while they are in foster care,” says Tracey Feild, director of the Foundation’s Child Welfare Strategy Group.